# Data source: https://www1.swarthmore.edu/NatSci/peverso1/Sports%20Data/JamesSteinData/Efron-Morris%20Baseball/EfronMorrisBB.txt

baseball = read.csv("../data/EfronMorrisBB.txt", sep = "\t", stringsAsFactors = FALSE) %>% dplyr::select(LastName,AtBats,BattingAverage,SeasonAverage)17 Statistical Learning Theory and Regularization

“In God we trust; all others must bring data.” — W. Edwards Deming

When AlphaGo defeated world champion Lee Sedol in 2016, its neural networks contained millions of parameters—far more than the number of training positions it had observed. How did it avoid simply memorizing the training data? The answer lies in regularization: the systematic imposition of constraints that prevent models from over-fitting to noise. This chapter reveals that regularization is not merely a computational trick but emerges naturally from Bayesian reasoning about uncertainty.

The development of learning algorithms has been driven by two fundamental paradigms: the classical frequentist approach centered around maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) and the Bayesian approach grounded in decision theory. This chapter explores how these seemingly distinct methodologies converge in modern AI theory, particularly through the lens of regularization and model selection.

Maximum likelihood estimation represents the cornerstone of classical statistical inference. Given observed data \(\mathcal{D} = (x_i, y_i)_{i=1}^n\) and a parametric model \(f_{\theta}(x)\), the MLE principle seeks to find the parameter values that maximize the likelihood function: \[ \hat{\theta}_{\mathrm{MLE}} = \arg\max_{\theta} L(\theta; \mathcal{D}) = \arg\max_{\theta} \prod_{i=1}^n p(y_i \mid x_i, \theta) \]

This approach has several appealing properties: it provides consistent estimators under mild conditions, achieves the Cramér-Rao lower bound asymptotically, and offers a principled framework for parameter estimation. These classical guarantees are typically stated under i.i.d. sampling assumptions; from a Bayesian perspective, exchangeability (Chapter 3) is a weaker condition that still supports learning from data in many settings. The Cramér-Rao bound is expressed in terms of Fisher information, and in exponential-family models Fisher information and sufficiency are closely related ways of formalizing how much information the data carry about a parameter.

However, MLE has well-documented limitations, particularly in high-dimensional settings. MLE can lead to overfitting, poor generalization, and numerical instability. Furthermore, as shown by Stein’s paradox, MLE can be inadmissible, meaning there are other estimators that have lower risk than the MLE. We will start this chapter with the normal means problem and demonstrate how MLE can be inadmissible.

17.1 Normal Means Problem

Consider the vector of means case where \(\theta = (\theta_1, \ldots, \theta_p)\). We have \[ \bar y_i \mid \theta_i \sim N(\theta_i, \sigma^2/n_i), \quad i=1,\ldots,p, \quad p > 2 \tag{17.1}\] Here \(\bar y_i\) is the mean of \(n_i\) observations, i.e., \(\bar y_i = \frac{1}{n_i} \sum_{j=1}^{n_i} y_{ij}\).

The goal is to estimate the vector of means \(\theta = (\theta_1, \ldots, \theta_p)\), and we can achieve this by borrowing strength across the observations.

This is also a proxy for non-parametric regression, where \(y_i = f(x_i) + \varepsilon_i\) and \(\theta_i = f(x_i)\). Much has been written on the properties of the Bayes risk as a function of \(n\) and \(p\), and extensive work has been done on the asymptotic properties of the Bayes risk as \(n\) and \(p\) grow to infinity.

The classical inference is based on the CLT \[ \hat \theta_i \mid \theta_i \sim N(\theta_i, \sigma^2/n_i), \] and the MLE estimate is given by \(\hat \theta_i = \bar y_i\). The MLE estimate is consistent and asymptotically normal, i.e., \[ \hat \theta_i \to N(\theta_i, \sigma^2/n_i) \quad \text{as} \quad n_i \to \infty. \]

On the other hand, the Bayes estimator is based on \(\theta_i \mid \hat \theta_i\), where \(\hat \theta_i = \bar y_i\). In other words, the classical approach is subject to the prosecutor’s fallacy—the logical error of confusing \(P(\text{data} \mid \text{hypothesis})\) with \(P(\text{hypothesis} \mid \text{data})\). Classical estimators are unbiased, whereas a Bayes estimator is biased.

Example 17.1 (Screening Corporate Performance) To illustrate the practical importance of the normal means problem, consider the challenge faced by investment analysts screening thousands of publicly traded companies for sustained superior performance (Polson and Scott 2012). Suppose we have return on assets (ROA) data for \(p = 53,038\) firms across 93 countries over 45 years. For each firm \(i\), we observe an average ROA performance \(\bar{y}_i\) over some time period.

The fundamental question is: Which firms have genuinely superior performance versus those that appear successful due to luck? This is precisely a massive multiple testing problem in the normal means framework. Using MLE, we would estimate each firm’s performance as \(\hat{\theta}_i = \bar{y}_i\) and declare any firm with \(\bar{y}_i > 0\) as superior. However, this approach ignores the massive multiplicity problem—with over 50,000 firms, many will appear successful purely by chance.

The Bayesian approach with appropriate shrinkage priors can distinguish between truly superior firms and those that are merely lucky. As we’ll see, this requires heavy-tailed priors that can accommodate the rare firms with genuine outperformance while shrinking the estimates of mediocre firms toward zero. This example demonstrates why the choice between MLE and Bayesian estimation has profound practical consequences in high-dimensional settings.

In practice, the normal means problem often requires careful preprocessing of the observed data. A common and crucial step is to normalize the observations by converting them to z-scores. This standardization serves multiple purposes and connects directly to the theoretical framework we’ve established.

Consider our corporate performance example where we observe ROA values \(\bar{y}_i\) for different firms. These firms may operate in different industries, countries, or time periods, making direct comparison problematic. Raw ROA values might range from -20% to +30%, with different scales and baseline expectations across sectors.

The z-score transformation standardizes each observation relative to a reference distribution: \[ z_i = \frac{\bar{y}_i - \mu_i}{\sigma_i}. \] where \(\mu_i\) and \(\sigma_i\) represent the mean and standard deviation estimated and predicted by an autoregressive model.

In the Polson & Scott study (Polson and Scott 2012), standardization was essential for handling the massive heterogeneity across their dataset of 53,038 firms spanning 93 countries and 45 years. The authors faced three critical challenges that z-score normalization helped address:

1. Cross-Country Comparisons: Raw ROA values varied dramatically across countries due to different accounting standards, economic conditions, and regulatory environments. A 5% ROA in Japan during the 1990s had very different implications than 5% ROA in Brazil during the same period.

2. Temporal Adjustments: Economic cycles, inflation rates, and market conditions changed substantially over the 45-year study period. The authors needed to adjust for these time-varying factors to identify firms with genuinely superior performance rather than those that simply operated during favorable periods.

3. Industry Heterogeneity: Different industries have fundamentally different ROA distributions. Technology firms typically show higher volatility and different baseline performance compared to utilities or manufacturing companies.

The authors implemented a sophisticated normalization procedure: \[ z_{i,t} = \frac{\text{ROA}_{i,t} - \mu_{\text{peer}(i),t}}{\sigma_{\text{peer}(i),t}} \]

where \(\text{peer}(i)\) represents firm \(i\)’s reference group (defined by industry, country, and size), and the subscript \(t\) indicates time-varying adjustments. This created standardized performance measures where:

- \(z_{i,t} = 0\) indicates performance exactly at the peer group median

- \(z_{i,t} = 1\) indicates performance one standard deviation above peers

- \(z_{i,t} = -1\) indicates performance one standard deviation below peers

After this rigorous standardization, the authors discovered a critical finding: sustained superior performance (\(\theta_i > 0\) consistently over time) was remarkably rare. Most firms showing high raw ROA were simply benefiting from favorable conditions rather than demonstrating genuine operational excellence. This finding emerged only after proper normalization—without standardization, hundreds of firms would have been incorrectly classified as superior performers.

The goal is to estimate the vector \(\theta\) using squared loss: \[ \mathcal{L}(\theta, \hat{\theta}) = \sum_{i=1}^p (\theta_i - \hat{\theta}_i)^2, \] where \(\hat{\theta}\) is the vector of estimates. We will compare the MLE estimate with the James-Stein estimate. A principled way to evaluate the performance of an estimator is to average its loss over the data; this metric is called the risk. The MLE estimate \(\hat{\theta}_i = y_i\) has a constant risk \(p\sigma^2\): \[ R(\theta,\hat{\theta}) = \E[y]{\mathcal{L}(\theta, \hat{\theta})} = \sum_{i=1}^p \E[y_i]{(y_i - \theta_i )^2}. \]

Here the expectation is over the data given by distribution Equation 17.1 and \(y_i \sim N(\theta_i, \sigma^2)\), we have \(\E[y_i]{(\theta_i - y_i)^2} = \Var{y_i} = \sigma^2\) for each \(i\). Therefore: \[ R(\theta,\hat{\theta}) = \sum_{i=1}^p \sigma^2 = p\sigma^2. \]

This shows that the MLE risk is constant and does not depend on the true parameter values \(\theta\), only on the dimension \(p\) and the noise variance \(\sigma^2\).

Given that MLE provides a natural baseline estimator with known risk properties, one might ask: can we do better? The Bayesian paradigm offers a fundamentally different perspective that often yields estimators with uniformly lower risk.

Bayesian inference offers a fundamentally different perspective by incorporating prior knowledge and quantifying uncertainty through probability distributions. The Bayesian approach begins with a prior distribution \(p(\theta)\) over the parameter space and updates this belief using Bayes’ rule: \[ p(\theta | y) = \frac{p(y | \theta) p(\theta)}{p(y)} \]

The Bayes estimator is the value \(\hat{\theta}^{B}\) that minimizes the Bayes risk, the expected loss: \[ \hat{\theta}^{B} = \arg\min_{\hat{\theta}(y)} R(\pi, \hat{\theta}(y)) \] Here \(\pi\) is the prior distribution of \(\theta\) and \(R(\pi, \hat{\theta}(y))\) is the Bayes risk defined as: \[ R(\pi, \hat{\theta}(y)) = \mathbb{E}_{\theta \sim \pi} \left[ \mathbb{E}_{y\mid \theta} \left[ \mathcal{L}(\theta, \hat{\theta}(y)) \right] \right]. \tag{17.2}\] For squared error loss, this yields the posterior mean \(\E{\theta \mid y}\), while for absolute error loss, it gives the posterior median.

For the normal means problem with squared error loss, this becomes: \[ R(\pi, \hat{\theta}(y)) = \int_{\theta \in \Theta} \left( \int_{y \in \mathcal{Y}} (\theta - \hat{\theta}(y))^2 p(y|\theta) dy \right) \pi(\theta) d\theta \]

The Bayes risk quantifies the expected performance of an estimator, taking into account both the uncertainty in the data and the prior uncertainty about the parameter. It serves as a benchmark for comparing different estimators: an estimator with lower Bayes risk is preferred under the chosen prior and loss function. In particular, the Bayes estimator achieves the minimum possible Bayes risk for the given prior and loss.

In 1961, Charles Stein and Willard James proved a startling result: they constructed an estimator for the mean of a multivariate normal distribution that uniformly dominates the sample mean under squared error loss—a finding that challenged what seemed like an elementary law of statistical theory. This result, now known as Stein’s paradox, demonstrates that for dimensions \(p \geq 3\), there always exists an estimator with strictly lower risk than the MLE for all parameter values.

The empirical evidence is striking: in applications ranging from baseball batting averages to toxoplasmosis prevalence rates to Pearson’s chi-square tests, the James-Stein estimator achieves mean squared errors less than half that of the sample mean. This result is paradoxical because it overturns the intuition that unbiased estimators should be optimal—despite introducing bias, the James-Stein estimator achieves strictly lower risk for all parameter values when \(p \geq 3\). The philosophical implications extend beyond estimation theory: by demonstrating that individual estimates can be improved by considering them jointly, Stein’s paradox provides deep connections to Bayesian thinking and the empirical Bayes framework.

Stein’s phenomenon where \(y_i \mid \theta_i \sim N(\theta_i, 1)\) and \(\theta_i \sim N(0, \tau^2)\) where \(\tau \rightarrow \infty\) illustrates this point well. The MLE approach is equivalent to the use of the improper “non-informative” uniform prior and leads to an estimator with poor risk properties.

Let \(\|y\|^2 = \sum_{i=1}^p y_i^2\) denote the squared Euclidean norm of \(y\). Then, we can make the following probabilistic statements from the model: \[ P\left( \| y \| > \| \theta \| \right) > \frac{1}{2} \] Now for the posterior, this inequality is reversed under a flat Lebesgue measure: \[ P\left( \| \theta \| > \| y \| \mid y \right) > \frac{1}{2} \] which is in conflict with the classical statement. This is a property of the prior which leads to a poor rule (the overall average) and risk.

The shrinkage rule (a.k.a. normal prior) where \(\tau^2\) is “estimated” from the data avoids this conflict. More precisely, we have: \[ \hat{\theta}(y) = \left( 1 - \frac{k-2}{\|y\|^2} \right) y \quad \text{and} \quad \E{\| \hat{\theta} - \theta \| } < k, \; \forall \theta. \] Hence, when \(\|y\|^2\) is small, the shrinkage factor is more extreme. For example, if \(k=10\), \(\|y\|^2=12\), then \(\hat{\theta} = (1/3) y\). Now we have the more intuitive result that: \[ P\left(\|\theta\| > \|y\| \mid y\right) < \frac{1}{2}. \]

This shows that careful specification of default priors matters in high dimensions.

The resulting estimator is called the James-Stein estimator and is a shrinkage estimator that shrinks the MLE towards the prior mean. The prior mean is typically the sample mean of the data. The James-Stein estimator is given by: \[ \hat{\theta}_{i}^{JS} = (1 - \lambda) \hat{\theta}_{i}^{MLE} + \lambda \bar{y}, \] where \(\lambda\) is a shrinkage parameter and \(\bar{y}\) is the sample mean of the data. The shrinkage parameter is typically chosen to minimize the risk of the estimator.

The key idea behind James-Stein shrinkage is that one can “borrow strength” across components. In this sense, the multivariate parameter estimation problem is easier than the univariate one.

Following Efron and Morris (1975), we can view the James-Stein estimator through the lens of empirical Bayes methodology. Efron and Morris demonstrate that Stein’s seemingly paradoxical result has a natural interpretation when viewed as an empirical Bayes procedure that estimates the prior distribution from the data itself.

Consider the hierarchical model: \[ \begin{aligned} y_i \mid \theta_i &\sim N(\theta_i, \sigma^2) \\ \theta_i \mid \mu, \tau^2 &\sim N(\mu, \tau^2) \end{aligned} \]

The marginal distribution of \(y_i\) is then \(y_i \sim N(\mu, \sigma^2 + \tau^2)\). In the empirical Bayes approach, we estimate the hyperparameters \(\mu\) and \(\tau^2\) from the marginal likelihood:

\[ m(y \mid \mu, \tau^2) = \prod_{i=1}^p \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi(\sigma^2 + \tau^2)}} \exp\left(-\frac{(y_i - \mu)^2}{2(\sigma^2 + \tau^2)}\right) \]

The maximum marginal likelihood estimators are: \[ \hat{\mu} = \bar{y} = \frac{1}{p}\sum_{i=1}^p y_i \] \[ \hat{\tau}^2 = \max\left(0, \frac{1}{p}\sum_{i=1}^p (y_i - \bar{y})^2 - \sigma^2\right) \]

The empirical Bayes estimator then becomes: \[ \hat{\theta}_i^{EB} = \frac{\hat{\tau}^2}{\sigma^2 + \hat{\tau}^2} y_i + \frac{\sigma^2}{\sigma^2 + \hat{\tau}^2} \hat{\mu} \]

This can be rewritten as: \[ \hat{\theta}_i^{EB} = \left(1 - \frac{\sigma^2}{\sigma^2 + \hat{\tau}^2}\right) y_i + \frac{\sigma^2}{\sigma^2 + \hat{\tau}^2} \bar{y} \]

When \(\mu = 0\) and using the estimate \(\hat{\tau}^2 = \max(0, \|y\|^2/p - \sigma^2)\), this reduces to a form closely related to the James-Stein estimator: \[ \hat{\theta}_i^{JS} = \left(1 - \frac{(p-2)\sigma^2}{\|y\|^2}\right) y_i \]

Efron and Morris show that the empirical Bayes interpretation provides insight into why the James-Stein estimator dominates the MLE. The key insight is that the MLE implicitly assumes an improper flat prior \(\pi(\theta) \propto 1\), which leads to poor risk properties in high dimensions.

The Bayes risk of the James-Stein estimator can be explicitly calculated due to the conjugacy of the normal prior and likelihood: \[ R(\theta, \hat{\theta}^{JS}) = p\sigma^2 - (p-2)\sigma^2 \mathbb{E}\left[\frac{1}{\|\theta + \epsilon\|^2/\sigma^2}\right] \]

where \(\epsilon \sim N(0, \sigma^2 I)\). Since the second term is always positive, we have: \[ R(\theta, \hat{\theta}^{JS}) < R(\theta, \hat{\theta}^{MLE}) \quad \forall \theta \in \mathbb{R}^p, \quad p \geq 3 \]

This uniform domination demonstrates the inadmissibility of the MLE under squared error loss for \(p \geq 3\).

In an applied problem, the gap in risk between MLE and JS estimators can be large. For example, in the normal means problem with \(p=100\) and \(n=100\), the risk of the MLE is \(R(\theta,\hat{\theta}_{MLE}) = 100\) while the risk of the JS estimator is \(R(\theta,\hat{\theta}_{JS}) = 1.5\). The JS estimator is 67 times more efficient than the MLE. The JS estimator is also minimax optimal in the sense that it attains the minimax risk bound for the normal means problem. The minimax risk bound is the smallest risk that can be attained by any estimator.

The James-Stein estimator illustrates how incorporating prior information (via shrinkage) can lead to estimators with lower overall risk compared to the MLE, especially in high-dimensional settings. However, it is not the only shrinkage estimator that dominates the MLE. Other shrinkage estimators, such as the ridge regression estimator, also have lower risk than the MLE. The key insight is that shrinkage estimators can leverage prior information to improve estimation accuracy, especially in high-dimensional settings.

Note, that we used the empirical Bayes version of the definition of risk. Full Bayes approach incorporates both the data and the prior distribution of the parameter as in Equation 17.2.

17.2 Unbiasedness and the Optimality of Bayes Rules

The optimal Bayes rule \(\delta_\pi(x) = \E{\theta \mid y}\) is the posterior mean under squared error loss. An interesting feature of the Bayes rule is that it is biased except in degenerate cases like improper priors, which can lose optimality properties. This can be seen using the following decomposition.

If the rule was unbiased, then the Bayes risk would be zero. This follows by contradiction: assume for the sake of argument that \(\E[x\mid\theta]{\delta_{\pi}(y)} = \theta\), then \[ r(\pi, \delta_{\pi}(y)) = \E[\pi]{\E[y\mid\theta]{(\delta_{\pi}(y) - \theta)^2}} = \E[\pi]{\theta^2} + \E[y]{\delta_{\pi}(y)}^2 - 2\E[\pi]{\theta \E[y\mid\theta]{\delta_{\pi}(y)}} = 0 \] which is a contradiction since the Bayes risk cannot be zero in non-degenerate cases.

The key feature of Bayes rules is the bias-variance tradeoff inherent in their nature. You achieve a large reduction in variance for a small amount of bias. This is the underpinning of James-Stein estimation.

Another interesting feature is that the Bayes rule \(\E{\theta \mid y}\) is always Bayes sufficient in the sense that \[ \E[\pi]{\theta \mid \E[\pi]{\theta \mid y}} = \E[\pi]{\theta \mid y} \] So conditioning on \(\E[\pi]{\theta \mid y}\) is equivalent to conditioning on \(y\) when estimating \(\theta\). This property is used in quantile neural network approaches to generative methods.

Example 17.2 (Example: James-Stein for Baseball Batting Averages) We reproduce the baseball batting average example from Efron and Morris (1977). Data below has the number of hits for 18 baseball players after 45 at-bats in 1970 season.

Now, we can estimate overall mean and variance

mu_hat <- mean(baseball$BattingAverage)

sigma2_hat <- var(baseball$BattingAverage)As well as the posterior mean for each player (James-Stein estimator)

baseball <- baseball %>%

mutate(

JS = (sigma2_hat / (sigma2_hat + (BattingAverage * (1 - BattingAverage) / AtBats))) * mu_hat +

((BattingAverage * (1 - BattingAverage) / AtBats) / (sigma2_hat + (BattingAverage * (1 - BattingAverage) / AtBats))) * BattingAverage

)

kable(baseball)| LastName | AtBats | BattingAverage | SeasonAverage | JS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clemente | 45 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.34 |

| Robinson | 45 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.32 |

| Howard | 45 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.31 |

| Johnstone | 45 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.30 |

| Berry | 45 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.29 |

| Spencer | 45 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.29 |

| Kessinger | 45 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.28 |

| Alvarado | 45 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.27 |

| Santo | 45 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.26 |

| Swaboda | 45 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.26 |

| Petrocelli | 45 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.25 |

| Rodriguez | 45 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.25 |

| Scott | 45 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.25 |

| Unser | 45 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.25 |

| Williams | 45 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Campaneris | 45 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.24 |

| Munson | 45 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.23 |

| Alvis | 45 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.22 |

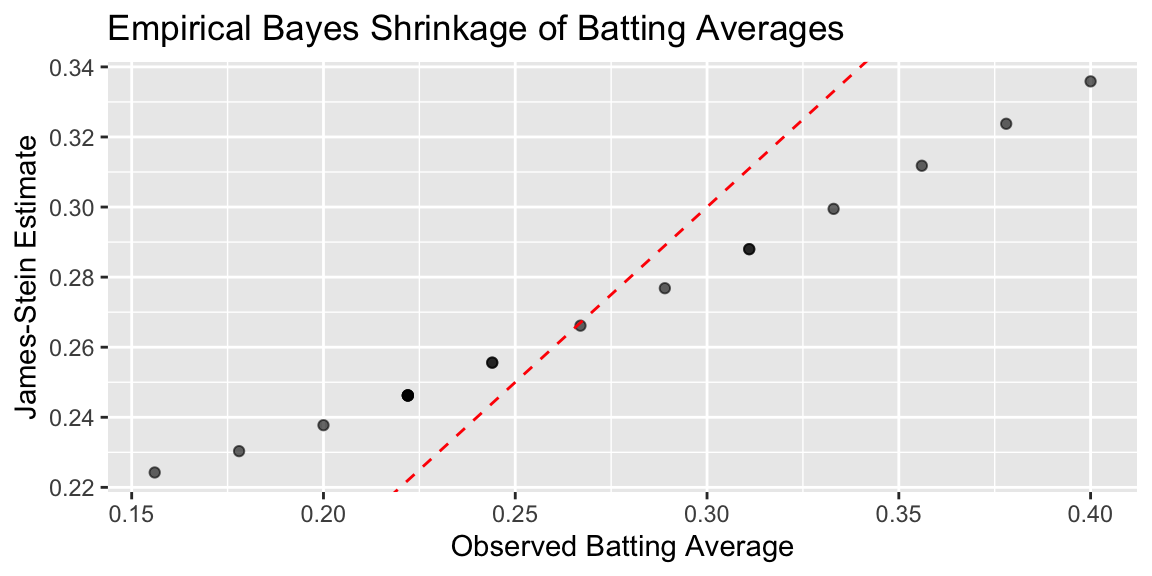

Plot below shows the observed averages vs. James-Stein estimate

Code

ggplot(baseball, aes(x = BattingAverage, y = JS)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.6) +

geom_abline(slope = 1, intercept = 0, linetype = "dashed", color = "red") +

labs(

x = "Observed Batting Average",

y = "James-Stein Estimate",

title = "Empirical Bayes Shrinkage of Batting Averages"

)

Calculate mean squared error (MSE) for observed and James-Stein estimates

mse_observed <- mean((baseball$BattingAverage - mu_hat)^2)

mse_js <- mean((baseball$JS - mu_hat)^2)

cat(sprintf("MSE (Observed): %.6f\n", mse_observed))

## MSE (Observed): 0.004584

cat(sprintf("MSE (James-Stein): %.6f\n", mse_js))

## MSE (James-Stein): 0.001031We can see that the James-Stein estimator has a lower MSE than the observed batting averages. This is a demonstration of Stein’s paradox, where the James-Stein estimator, which shrinks the estimates towards the overall mean, performs better than the naive sample mean estimator.

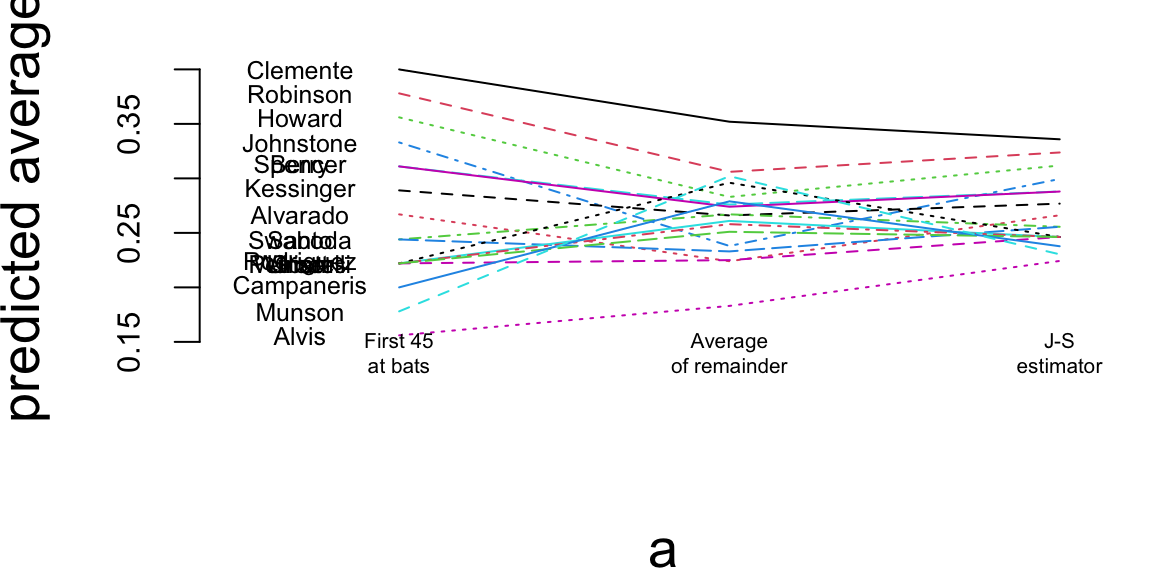

Code

a = matrix(rep(1:3, nrow(baseball)), 3, nrow(baseball))

b = matrix(c(baseball$BattingAverage, baseball$SeasonAverage, baseball$JS), 3, nrow(baseball), byrow=TRUE)

matplot(a, b, pch=" ", ylab="predicted average", xaxt="n", xlim=c(0.5, 3.1), ylim=c(0.13, 0.42))

matlines(a, b)

text(rep(0.7, nrow(baseball)), baseball$BattingAverage, baseball$LastName, cex=0.6)

text(1, 0.14, "First 45\nat bats", cex=0.5)

text(2, 0.14, "Average\nof remainder", cex=0.5)

text(3, 0.14, "J-S\nestimator", cex=0.5)

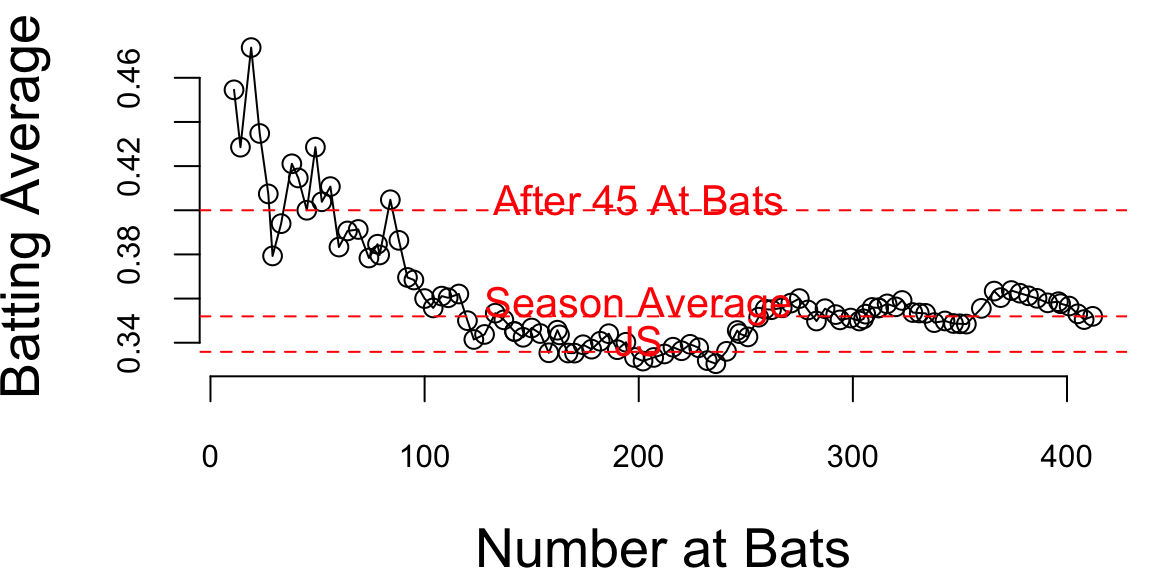

Now if we look at the season dynamics for Clemente

Code

# Data source: https://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/hittinglogs.php?p=clemero01&y=1970

cl = read.csv("../data/clemente.csv")

x = cumsum(cl$AB)

y = cumsum(cl$H)/cumsum(cl$AB)

# Plot x,y starting from index 2

ind = c(1,2)

plot(x[-ind],y[-ind], type='o', ylab="Batting Average", xlab="Number at Bats", pch=21, bg="lightblue", cex=0.8, lwd=2)

# Add horizontal line for season average 145/412 and add text above line `Season Average`

text(200, 145/412 + 0.005, "Season Average", col = "red")

abline(h = 145/412, col = "red", lty = 2)

# Ted williams record is .406 in 1941, so you know the first data points are noise

text(200, baseball$JS[1] + 0.005, "JS", col = "red")

abline(h = baseball$JS[1], col = "red", lty = 2)

text(200, baseball$BattingAverage[1] + 0.005, "After 45 At Bats", col = "red")

abline(h = baseball$BattingAverage[1], col = "red", lty = 2)

Full Bayes Shrinkage

The alternative approach to the regularization is to use full Bayes, which places a prior distribution on the parameters and computes the full posterior distribution using the Bayes rule: \[ p( \theta \mid \tau, y ) = \frac{ f( y | \theta ) p( \theta \mid \tau ) }{ m(y \mid \tau) }, \] here \[ m(y \mid \tau) = \int f( y\mid \theta ) p( \theta \mid \tau ) d \theta, \] Here \(m(y \mid \tau)\) is the marginal beliefs about the data.

The empirical Bayes approach is to estimate the prior distribution \(p( \theta \mid \tau )\) from the data. This can be done by maximizing the marginal likelihood \(m(y \mid \tau )\) with respect to \(\tau\). The resulting estimator is called the type II maximum likelihood estimator (MMLE). \[ \hat{\tau} = \arg \max_{\tau} \log m( y \mid \tau ). \]

For example, in the normal-normal model, when \(\theta \sim N(\mu,\tau^2)\) with \(\mu=0\), we can integrate out the high dimensional \(\theta\) and find \(m(y | \tau)\) in closed form as \(y_i \sim N(0, \sigma^2 + \tau^2)\) \[ m( y | \tau ) = ( 2 \pi)^{-n/2} ( \sigma^2 + \tau^2 )^{- n/2} \exp \left ( - \frac{ \sum y_i^2 }{ 2 ( \sigma^2 + \tau^2) } \right ) \] The original JS estimator shrinks to zero and estimates prior variance using empirical Bayes (marginal MLE or Type II MLE). Efron and Morris and Lindley showed that you want to shrink to overall mean \(\bar y\) and in this approach \[ \theta \sim N(\mu,\tau^2). \] The original JS is \(\mu=0\). To estimate the \(\mu\) and \(\tau\) you can do full Bayes or empirical Bayes that shrinks to overall grand mean \(\bar y\), which serves as the estimate of the original prior mean \(\mu\). It seems paradoxical that you estimate prior parameters from the data. However, this is not the case. You simply use mixture prior Diaconis and Ylvisaker (1983) with marginal MLE (MMLE). The MMLE is the product \[ \int_{\theta_i}\prod_{i=1}^k p(\bar y_i \mid \theta_i)p(\theta_i \mid \mu, \tau^2). \]

The motivation for the shrinkage prior rather than a flat uniform prior are the following probabilistic arguments. They have an ability to balance signal detection and noise suppression in high-dimensional settings. Unlike flat uniform priors, shrinkage priors adaptively shrink small signals towards zero while preserving large signals. This behavior is crucial for sparse estimation problems, where most parameters are expected to be zero or near-zero. The James-Stein procedure is an example of global shrinkage, when the overall sparsity level across all parameters is controlled, ensuring that the majority of parameters are shrunk towards zero. Later in this section we will discuss local shrinkage priors, such as the horseshoe prior, which allow individual parameters to escape shrinkage if they represent significant signals.

In summary, flat uniform priors (MLE) fail to provide adequate regularization in high-dimensional settings, leading to poor risk properties and overfitting. By incorporating probabilistic arguments and hierarchical structures, shrinkage priors offer a principled approach to regularization that aligns with Bayesian decision theory and modern statistical practice.

17.3 Bias-Variance Decomposition

The discussion of shrinkage priors and James-Stein estimation naturally leads us to a fundamental concept in statistical learning: the bias-variance decomposition. This decomposition provides the theoretical foundation for understanding why shrinkage methods like James-Stein can outperform maximum likelihood estimation, even when they introduce bias.

The key insight is that estimation error can be decomposed into two components: bias (systematic error) and variance (random error). While unbiased estimators like maximum likelihood have zero bias, they often suffer from high variance, especially in high-dimensional settings. Shrinkage methods intentionally introduce a small amount of bias to achieve substantial reductions in variance, leading to better overall performance.

This trade-off between bias and variance is not just a theoretical curiosity—it’s the driving force behind many successful machine learning algorithms, from ridge regression to neural networks with dropout. Understanding this decomposition helps us make principled decisions about model complexity and regularization.

For parameter estimation, we can decompose the mean squared error as follows: \[ \begin{aligned} \E{(\hat{\theta} - \theta)^2} &= \E{(\hat{\theta} - \E{\hat{\theta}} + \E{\hat{\theta}} - \theta)^2} \\ &= \E{(\hat{\theta} - \E{\hat{\theta}})^2} + \E{(\E{\hat{\theta}} - \theta)^2} \\ &= \text{Var}(\hat{\theta}) + \text{Bias}(\hat{\theta})^2 \end{aligned} \] The cross term has expectation zero.

For prediction problems, we have \(y = \theta + \epsilon\) where \(\epsilon\) is independent with \(\text{Var}(\epsilon) = \sigma^2\). Hence \[ \E{(y - \hat{y})^2} = \sigma^2 + \E{(\hat{\theta} - \theta)^2} \]

This decomposition shows that prediction error consists of irreducible noise, estimation variance, and estimation bias. Bayesian methods typically trade a small increase in bias for a substantial reduction in variance, leading to better overall performance.

The bias-variance decomposition provides a framework for understanding estimation error, but it doesn’t tell us how to construct optimal estimators. To find the best decision rule—whether for estimation, hypothesis testing, or model selection—we need a more general framework that can handle different types of loss functions and prior information. This leads us to Bayesian decision theory and the concept of risk decomposition.

Risk Decomposition

How does one find an optimal decision rule? It could be a test region, an estimation procedure or the selection of a model. Bayesian decision theory addresses this issue.

The a posteriori Bayes risk approach is as follows. Let \(\delta(x)\) denote the decision rule. Given the prior \(\pi(\theta)\), we can simply calculate \[ R_n ( \pi , \delta ) = \int_x m( x ) \left \{ \int_\Theta \mathcal{L}( \theta , \delta(x) ) p( \theta | x ) d \theta \right \} d x . \] Then the optimal Bayes rule is to pointwise minimize the inner integral (a.k.a. the posterior Bayes risk), namely \[ \delta^\star ( x ) = \arg \max_\delta \int_\Theta \mathcal{L}( \theta , \delta(x) ) p( \theta | x ) d \theta . \] The caveat is that this gives us no intuition into the characteristics of the prior which are important. Moreover, we do not need the marginal beliefs \(m(x)\).

For example, under squared error estimation loss, the optimal estimator is simply the posterior mean, \(\delta^\star (x) = E( \theta | x )\). The properties of this optimal rule—including its inherent bias and the bias-variance tradeoff it embodies—were established in Section 17.2.

17.4 Sparsity

Let the true parameter be sparse with the form \(\theta_p = \left( \sqrt{d/p}, \ldots, \sqrt{d/p}, 0, \ldots, 0 \right)\). The problem of recovering a vector with many zero entries is called sparse signal recovery. The “ultra-sparse” or “nearly black” vector case occurs when \(p_n\), denoting the number of non-zero parameter values, satisfies \(\theta \in l_0[p_n]\), which denotes the set \(\#(\theta_i \neq 0) \leq p_n\) where \(p_n = o(n)\) and \(p_n \rightarrow \infty\) as \(n \rightarrow \infty\).

High-dimensional predictor selection and sparse signal recovery are routine statistical and machine learning tasks and present a challenge for classical statistical methods. Historically, James-Stein estimation (or \(\ell_2\)-regularization) functions as a global shrinkage rule. Because it lacks local parameters to adapt to sparsity, it struggles to recover sparse signals effectively.

James-Stein is equivalent to the model: \[ y_i = \theta_i + \epsilon_i \quad \text{and} \quad \theta_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \tau^2) \] For the sparse \(r\)-spike problem, \(\hat{\theta}_{JS}\) performs poorly and we require a different rule. rather than using softmax For \(\theta_p\) we have: \[ \frac{p \|\theta\|^2}{p + \|\theta\|^2} \leq R(\hat{\theta}^{JS}, \theta_p) \leq 2 + \frac{p \|\theta\|^2}{d + \|\theta\|^2}. \] This implies that \(R(\hat{\theta}^{JS}, \theta_p) \geq (p/2)\).

In the sparse case, a simple thresholding rule can beat MLE and JS when the signal is sparse. Assuming \(\sigma^2 = 1\), the thresholding estimator is: \[ \hat{\theta}_{thr} = \begin{cases} \hat{\theta}_i & \text{if } \hat{\theta}_i > \sqrt{2 \ln p} \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \] This simple example shows that the choice of penalty should not be taken for granted as different estimators will have different risk profiles.

One such estimator that achieves the optimal minimax rate is the horseshoe estimator Carvalho, Polson, and Scott (2010), which we discuss in detail in Section 17.10. It is a local shrinkage estimator that dominates the sample mean in MSE and has good posterior concentration properties for sparse signal problems.

17.5 Maximum A posteriori Estimation (MAP) and Regularization

Having established that Bayesian shrinkage reduces estimation risk, we now examine a computationally tractable alternative: maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation. While Bayesian shrinkage provably reduces estimation risk, full posterior inference can be computationally demanding. Maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation offers a tractable alternative that captures many regularization benefits without the cost of full integration. MAP captures the regularization benefits of Bayesian methods without requiring full posterior inference.

Given input-output pairs \((x_i,y_i)\), MAP learns the function \(f\) that maps inputs \(x_i\) to outputs \(y_i\) by minimizing \[ \underset{f}{\mathrm{minimize}} \quad \sum_{i=1}^N \mathcal{L}(y_i,f(x_i)) + \lambda \phi(f). \] The first term is the loss function that measures the difference between the predicted output \(f(x_i)\) and the true output \(y_i\). The second term is a regularization term that penalizes complex functions \(f\) to prevent overfitting. The parameter \(\lambda\) controls the trade-off between fitting the data well and keeping the function simple. In the case when \(f\) is a parametric model, then we simply replace \(f\) with the parameters \(\theta\) of the model, and the regularization term becomes a penalty on the parameters.

The loss is simply a negative log-likelihood from a probabilistic model specified for the data generating process. For example, when \(y\) is numeric and \(y_i \mid x_i \sim N(f(x_i),\sigma^2)\), we get the squared loss \(\mathcal{L}(y,f(x)) = (y-f(x))^2\). When \(y_i\in \{0,1\}\) is binary, we use the logistic loss \(\mathcal{L}(y,f(x)) = \log(1+\exp(-yf(x)))\).

The penalty term \(\lambda \phi(f)\) discourages complex functions \(f\). Then, we can think of regularization as a technique to incorporate some prior knowledge about parameters of the model into the estimation process. Consider an example when regularization allows us to solve a hard problem of filtering noisy traffic data.

Example 17.3 (Traffic) Consider traffic flow speed measured by an in-ground sensor installed on interstate I-55 near Chicago. Speed measurements are noisy and prone to have outliers. Figure 17.1 shows measured speed data, averaged over five minute intervals on one of the weekdays.

The statistical model is \[ y_t = f_t + \epsilon_t, ~ \epsilon_t \sim N(0,\sigma^2), ~ t=1,\ldots,n, \] where \(y_t\) is the speed measurement at time \(t\), \(f_t\) is the true underlying speed at time \(t\), and \(\epsilon_t\) is the measurement noise. There are two sources of noise. The first is the measurement noise, caused by the inherent nature of the sensor’s hardware. The second source is due to sampling error, vehicles observed on a specific lane where the sensor is installed might not represent well traffic in other lanes. A naive MLE approach would be to estimate the speed profile \(f = (f_1, \ldots, f_n)\) by minimizing the squared loss \[ \hat f = \arg\min_{f} \sum_{t=1}^{n} (y_t - f_t)^2. \] However, the minima of this loss function is 0 and corresponds to the case when \(\hat f_t = y_t\) for all \(t\). We have learned nothing about the speed profile, and the estimate is simply the noisy observation \(y_t\). In this case, we have no way to distinguish between the true speed profile and the noise.

However, we can use regularization and bring some prior knowledge about traffic speed profiles to improve the estimate of the speed profile and to remove the noise.

Specifically, we will use a trend filtering approach. Under this approach, we assume that the speed profile \(f\) is a piece-wise linear function of time, and we want to find a function that captures the underlying trend while ignoring the noise. The regularization term \(\phi(f)\) is then the second difference of the speed profile, \[ \lambda \sum_{t=1}^{n-1}|f_{t-1} - 2f_t + f_{t+1}| \] which penalizes the “kinks” in the speed profile. The value of this penalty is zero, when \(f_{t-1}, f_t, f_{t+1}\) lie on a straight line, and it increases when the speed profile has a kink. The parameter \(\lambda\) is a regularization parameter that controls the strength of the penalty.

Trend filtering penalized function is then \[ (1/2) \sum_{t=1}^{n}(y_t - f_t)^2 + \lambda \sum_{t=1}^{n-1}|f_{t-1} - 2f_t + f_{t+1}|, \] which is a variation of a well-known Hodrick-Prescott filter.

This approach requires us to choose the regularization parameter \(\lambda\). A small value of \(\lambda\) will lead to a function that fits the data well, but may not capture the underlying trend. A large value of \(\lambda\) will lead to a function that captures the underlying trend, but may not fit the data well. The optimal value of \(\lambda\) can be chosen using cross-validation or other model selection techniques. The left panel of Figure 17.2 shows the trend filtering for different values of \(\lambda \in \{5,50,500\}\). The right panel shows the optimal value of \(\lambda\) chosen by cross-validation (by visual inspection).

17.6 The Duality Between Regularization and Priors

A large number of statistical problems can be expressed in the canonical optimization form:

\[ \begin{aligned} & \underset{x \in \mathbb{R}^d}{\text{minimize}} & & l(x) + \phi(x) \end{aligned} \tag{17.3}\]

Perhaps the most common example arises in estimating the regression coefficients \(x\) in a generalized linear model. Here \(l(x)\) is a negative log likelihood or some other measure of fit, and \(\phi(x)\) is a penalty function that effects a favorable bias-variance tradeoff.

From the Bayesian perspective, \(l(x)\) and \(\phi(x)\) correspond to the negative logarithms of the sampling model and prior distribution in the hierarchical model:

\[ p(y \mid x) \propto \exp\{-l(x)\}, \quad p(x) \propto \exp\{-\phi(x)\} \tag{17.4}\]

and the solution to Equation 17.3 may be interpreted as a maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate.

Another common case is where \(x\) is a variable in a decision problem where options are to be compared on the basis of expected loss, and where \(l(x)\) and \(\phi(x)\) represent conceptually distinct contributions to the loss function. For example, \(l(x)\) may be tied to the data, and \(\phi(x)\) to the intrinsic cost associated with the decision.

MAP as a Poor Man’s Bayesian

There is a duality between using regularization term in optimization problem and assuming a prior distribution over the parameters of the model \(f\). Given the likelihood \(L(y_i,f(x_i))\), the posterior is given by Bayes’ rule: \[ p(f \mid y, x) = \frac{\prod_{i=1}^n L(y_i,f(x_i)) p(f)}{p(y \mid x)}. \] If we take the negative log of this posterior, we get: \[ -\log p(f \mid y, x) = - \sum_{i=1}^n \log L(y_i,f(x_i)) - \log p(f) + \log p(y \mid x). \] Since loss is the negative log-likelihood \(\mathcal{L}(y_i,f(x_i)) = -\log L(y_i,f(x_i))\), the posterior maximization is equivalent to minimizing the following regularized loss function: \[ \sum_{i=1}^n \mathcal{L}(y_i,f(x_i)) - \log p(f). \] The last term \(\log p(y_i \mid x_i)\) does not depend on \(f\) and can be ignored in the optimization problem. Thus, the equivalence is given by: \[ \lambda \phi(f) = -\log p(f), \] where \(\phi(f)\) is the penalty term that corresponds to the prior distribution of \(f\). Below we will consider several choices for the prior distribution of \(f\) and the corresponding penalty term \(\phi(f)\) commonly used in practice.

17.7 Ridge Regression (\(\ell_2\) Norm)

Tikhonov Regularization Framework

The Tikhonov regularization framework provides a general setting for regression that connects classical regularization theory with modern Bayesian approaches. Given observed data \((x_i, y_i)_{i=1}^n\) and a parametric model \(f(x,w)\) with parameter vector \(w \in \mathbb{R}^k\), we define a data misfit functional: \[ E_D(w) = \sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - f(x_i,w))^2 \]

This yields a Gaussian likelihood: \[ p(y \mid w) = \frac{1}{Z_D}\exp\left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}E_D(w)\right) \] where \(\sigma^2\) denotes the noise variance and \(Z_D\) is a normalization constant.

A Gaussian prior on the weights can be specified as: \[ p(w) = \frac{1}{Z_W}\exp\left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma_w^2}E_W(w)\right) \] where \(E_W(w)\) denotes a quadratic penalty on \(w\) (e.g., \(E_W(w) = w^T w\)), \(\sigma_w^2\) is the prior variance, and \(Z_W\) is its normalization constant.

The hyperparameters \(\sigma^2\) and \(\sigma_w^2\) control the strength of the noise and the prior. Following MacKay’s notation, we define precisions \(\tau_D^2 = 1/\sigma^2\) and \(\tau_w^2 = 1/\sigma_w^2\). Let \(B\) and \(C\) denote the Hessians of \(E_D(w)\) and \(E_W(w)\) at the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate \(w^{\text{MAP}}\). The Hessian of the negative log-posterior is then \(A = \tau_w^2 C + \tau_D^2 B\).

Evaluating the log-evidence under a Gaussian Laplace approximation yields: \[ \log p(D \mid \tau_w^2,\tau_D^2) = -\tau_w^2 E_W^{\text{MAP}} - \tau_D^2 E_D^{\text{MAP}} - \frac{1}{2}\log\det A - \log Z_W(\tau_w^2) - \log Z_D(\tau_D^2) + \frac{k}{2}\log(2\pi) \]

The associated Occam factor, which penalizes excessively small prior variances, is: \[ -\tau_w^2 E_W^{\text{MAP}} - \frac{1}{2}\log\det A - \log Z_W(\tau_w^2) \]

This represents the reduction in effective volume of parameter space from prior to posterior.

[!NOTE] Notation: In the previous sections on Normal Means, we used \(\theta\) to denote the parameters. In the context of regression, we will follow standard convention and use \(\beta\) to denote the vector of coefficients.

The ridge regression uses a Gaussian prior on the parameters of the model \(f\), which leads to a squared penalty term. Specifically, we assume that the parameters \(\beta\) of the model \(f(x) = x^T\beta\) are distributed as: \[ \beta \sim N(0, \sigma_\beta^2 I), \] where \(I\) is the identity matrix and \(\sigma_\beta^2\) is the prior variance (distinct from the noise variance \(\sigma^2\)). The prior distribution of \(\beta\) is a multivariate normal distribution with mean 0 and covariance \(\sigma_\beta^2 I\). The negative log of this prior distribution is given by: \[ -\log p(\beta) = \frac{1}{2\sigma_\beta^2} \|\beta\|_2^2 + \text{const}, \] where \(\|\beta\|_2^2 = \sum_{j=1}^p \beta_j^2\) is the squared 2-norm of the vector \(\beta\). The regularization term \(\phi(f)\) is then given by: \[ \phi(f) = \frac{1}{2\sigma_\beta^2} \|\beta\|_2^2. \] This leads to the following optimization problem: \[ \underset{\beta}{\mathrm{minimize}}\quad \|y- X\beta\|_2^2 + \lambda \|\beta\|_2^2, \] where \(\lambda = 1/\sigma^2\) is the regularization parameter that controls the strength of the prior. The solution to this optimization problem is given by: \[ \hat{\beta}_{\text{ridge}} = ( X^T X + \lambda I )^{-1} X^T y. \] The regularization parameter \(\lambda\) is related to the variance of the prior distribution. When \(\lambda=0\), the function \(f\) is the maximum likelihood estimate of the parameters. When \(\lambda\) is large, the function \(f\) is the prior mean of the parameters. When \(\lambda\) is infinite, the function \(f\) is the prior mode of the parameters.

Notice, that the OLS estimate (invented by Gauss) is a special case of ridge regression when \(\lambda = 0\): \[ \hat{\beta}_{\text{OLS}} = ( X^T X )^{-1} X^T y. \]

The original motivation for ridge regularization was to address the problem of numerical instability in the OLS solution when the design matrix \(X\) is ill-conditioned, i.e. when \(X^T X\) is close to singular. In this case, the OLS solution can be very sensitive to small perturbations in the data, leading to large variations in the estimated coefficients \(\hat{\beta}\). This is particularly problematic when the number of features \(p\) is large, as the condition number of \(X^T X\) can grow rapidly with \(p\). The ridge regression solution stabilizes the OLS solution by adding a small positive constant \(\lambda\) to the diagonal of the \(X^T X\) matrix, which improves the condition number and makes the solution more robust to noise in the data. The additional term \(\lambda I\) simply shifts the eigenvalues of \(X^T X\) away from zero, thus improving the numerical stability of the inversion.

Another way to think and write the objective function of Ridge as the following constrained optimization problem: \[ \underset{\beta}{\mathrm{minimize}}\quad \|y- X\beta\|_2^2 \quad \text{subject to} \quad \|\beta\|_2^2 \leq t, \] where \(t\) is a positive constant that controls the size of the coefficients \(\beta\). This formulation emphasizes the idea that ridge regression is a form of regularization that constrains the size of the coefficients, preventing them from growing too large and leading to overfitting. The constraint \(\|\beta\|_2^2 \leq t\) can be interpreted as a budget on the size of the coefficients, where larger values of \(t\) allow for larger coefficients and more complex models.

Constraint on the model parameters (and the original Ridge estimator) was proposed by Tikhonov et al. (1943) for solving inverse problems to “discover” physical laws from observations. The norm of the \(\beta\) vector would usually represent amount of energy required. Many processes in nature are energy minimizing!

Again, the tuning parameter \(\lambda\) controls trade-off between how well model fits the data and how small \(\beta\)s are. Different values of \(\lambda\) will lead to different models. We select \(\lambda\) using cross validation.

Example 17.4 (Shrinkage) Consider a simulated data with \(n=50\), \(p=30\), and \(\sigma^2=1\). The true model is linear with \(10\) large coefficients between \(0.5\) and \(1\).

Our approximators \(\hat f_{\beta}\) is a linear regression. We can empirically calculate the bias by calculating the empirical squared loss \(1/n\|y -\hat y\|_2^2\) and variance can be empirically calculated as \(1/n\sum (\bar{\hat{y}} - \hat y_i)^2\)

Bias squared \(\mathrm{Bias}(\hat{y})^2=0.006\) and variance \(\Var{\hat{y}} =0.627\). Thus, the prediction error = \(1 + 0.006 + 0.627 = 1.633\)

We’ll do better by shrinking the coefficients to reduce the variance. Let’s estimate how big a gain we can achieve with Ridge regression.

The figure below shows the distribution of true coefficient values used to generate the data. The histogram reveals a bimodal structure: approximately 20 coefficients are exactly zero (the tall bar at 0.0), while 10 coefficients are non-zero with values concentrated between 0.5 and 1.0. This sparse structure, where most features are irrelevant and only a subset truly matter for prediction, is common in many real-world problems such as genomics, text analysis, and high-dimensional sensor data.

The key question is: what value of the regularization parameter \(\lambda\) should we choose? Too small, and we don’t shrink enough to reduce variance; too large, and we introduce excessive bias by shrinking the true non-zero coefficients toward zero. The optimal choice balances these competing concerns.

Figure 17.3 (a) shows how prediction error varies with the amount of shrinkage (controlled by \(\lambda\)). The horizontal dashed line represents the constant prediction error of 1.633 from ordinary linear regression (OLS). The red curve shows Ridge regression’s prediction error as we increase regularization. At low shrinkage (left side), Ridge behaves similarly to OLS with high variance. As we increase shrinkage, the prediction error decreases substantially, reaching a minimum around \(\lambda \approx 5\). Beyond this point, excessive shrinkage introduces too much bias, and prediction error begins to rise again. The U-shaped curve is characteristic of the bias-variance trade-off: we need enough regularization to stabilize predictions, but not so much that we distort the true signal.

Figure 17.3 (b) decomposes Ridge regression’s prediction error into its constituent parts as a function of \(\lambda\). The black dashed horizontal line at approximately 1.0 represents the irreducible error from noise in the data. The blue curve (Ridge Var) shows variance decreasing monotonically as \(\lambda\) increases: stronger regularization makes the model more stable across different training sets. The red curve (Ridge Bias\(^2\)) shows squared bias increasing as \(\lambda\) grows: we move further from the true model by shrinking coefficients. The black curve (Ridge MSE) is the sum of these components plus the irreducible error. The optimal \(\lambda\) occurs where the rate of variance reduction exactly balances the rate of bias increase, minimizing total prediction error.

At the optimal value of \(\lambda\), Ridge regression achieves squared bias of 0.077 and variance of 0.402, yielding a total prediction error of \(1 + 0.077 + 0.402 = 1.48\). Compare this to the OLS solution with squared bias of 0.006 and variance of 0.627, giving prediction error of \(1 + 0.006 + 0.627 = 1.633\). By accepting a modest increase in bias (from 0.006 to 0.077), we achieve a substantial reduction in variance (from 0.627 to 0.402), resulting in an overall improvement of approximately 9% in prediction error.

This example illustrates a fundamental principle in statistical learning: the best predictor is not necessarily the one that fits the training data most closely. By deliberately introducing bias through regularization, we can build models that generalize better to new data. The Bayesian perspective makes this trade-off explicit: the prior distribution encodes our belief that coefficients should be small, and the posterior balances this belief against the evidence in the data.

Kernel View of Ridge Regression

Another interesting view stems from what is called the push-through matrix identity: \[ (aI + UV)^{-1}U = U(aI + VU)^{-1} \] for \(a\), \(U\), \(V\) such that the products are well-defined and the inverses exist. We can obtain this from \(U(aI + VU) = (aI + UV)U\), followed by multiplication by \((aI + UV)^{-1}\) on the left and the right. Applying the identity above to the ridge regression solution with \(a = \lambda\), \(U = X^T\), and \(V = X\), we obtain an alternative form for the ridge solution: \[ \hat{\beta} = X^T (XX^T + \lambda I)^{-1} Y. \] This is often referred to as the kernel form of the ridge estimator. From this, we can see that the ridge fit can be expressed as \[ X\hat{\beta} = XX^T (XX^T + \lambda I)^{-1} Y. \] What does this remind you of? This is precisely \(K(K + \lambda I)^{-1}Y\) where \(K = XX^T\), which, recall, is the fit from RKHS regression with a linear kernel \(k(x, z) = x^T z\). Therefore, we can think of RKHS regression as generalizing ridge regression by replacing the standard linear inner product with a general kernel. (Indeed, RKHS regression is often called kernel ridge regression.)

17.8 Scale Mixtures Representations

Why should we care about expressing distributions as mixtures? The answer lies in computational tractability and theoretical insight. Many important priors used in sparse estimation—including the Laplace (Lasso), horseshoe, and logistic—can be represented as Gaussian distributions with random variance. This representation is far more than a mathematical curiosity: it enables efficient Gibbs sampling algorithms where each conditional distribution has a closed form, and it reveals deep connections between seemingly different regularization approaches.

Scale mixtures of normals provide a powerful framework for constructing flexible priors and computational algorithms in Bayesian statistics. The key insight is that many useful distributions can be represented as Gaussian distributions with random variance, leading to tractable MCMC algorithms and analytical insights.

The Vertical Likelihood Duality

For computational efficiency in model evaluation, consider the problem of estimating \(\int_{\mathcal{X}} L(x) P(dx)\) where \(L: \mathcal{X} \to \mathbb{R}\). By letting \(Y = L(x)\), we can transform this to a one-dimensional integral \(\int_0^1 F_Y^{-1}(s) ds\).

We therefore have a duality: \[ \int_{\mathcal{X}} L(x) P(dx) = \int_0^1 F_Y^{-1}(s) ds \] where \(Y\) is a random variable \(Y = L(X)\) with \(X \sim P(dx)\).

This approach offers several advantages:

- We can use sophisticated grids (Riemann) to approximate one-dimensional integrals

- A grid on inverse CDF space is equivalent to importance weighting in the original \(\mathcal{X}\) space

- If \(F_Y^{-1}(s)\) is known and bounded, we could use deterministic grids on \([0,1]\) with \(O(N^{-4})\) convergence properties

The main caveats are:

- \(F_Y^{-1}(s)\) is typically unknown

- It becomes infinite if \(L\) is unbounded

- We often resort to stochastic Riemann sums

The duality implies that finding a good importance function on \([0,1]\) corresponds to finding good “weighting” in \(\mathcal{X}\) space. As a diagnostic for any importance sampling scheme, you should plot the equivalent grid on \([0,1]\) and estimated values of \(F_Y^{-1}\) to assess performance.

Fundamental Integral Identities

The two key integral identities for hyperbolic/GIG (Generalized Inverse Gaussian) and Pólya mixtures are: \[ \begin{aligned} \frac{\alpha^2 - \kappa^2}{2\alpha} e^{-\alpha|\theta - \mu| + \kappa(\theta - \mu)} &= \int_0^\infty \phi\left(\theta \mid \mu + \kappa\omega, \omega\right) p_{\text{gig}}\left(\omega \mid 1, 0, \sqrt{\alpha^2 - \kappa^2}\right) d\omega \\ \frac{1}{B(\alpha,\kappa)} \frac{e^{\alpha(\theta - \mu)}}{(1 + e^{\theta - \mu})^{2(\alpha - \kappa)}} &= \int_0^\infty \phi\left(\theta \mid \mu + \kappa\omega, \omega\right) p_{\text{pol}}(\omega \mid \alpha, \alpha - 2\kappa) d\omega \end{aligned} \] where \(p_{\text{pol}}\) denotes the Pólya density and \(p_{\text{gig}}\) the GIG density.

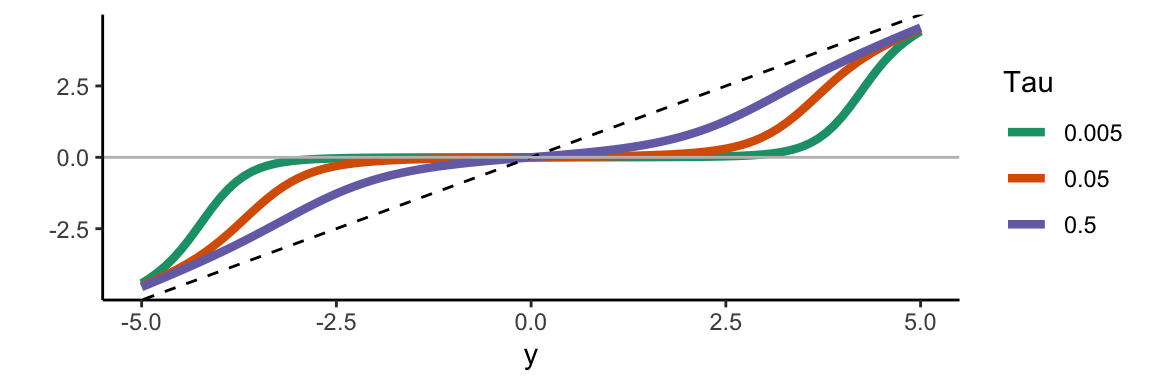

Quantile Regression Example

To illustrate these integral identities in practice, consider quantile regression. Start by choosing \(q \in (0,1)\) and define the quantile loss function \(l(x) = |x| + (2q-1)x\). This is also known as the check loss or hinge loss function, and is used in quantile regression for the \(q\)th quantile Koenker (2005). Johannes, Polson, and Yae (2009) represent this as a pseudo-likelihood involving the asymmetric Laplace distribution.

We can derive the corresponding envelope representation as a variance-mean Gaussian mixture. Let \(\kappa = 2q-1\). Then \(g(x) = l(x) + \kappa x = |x|\) is symmetric in \(x\) and concave in \(x^2\). Using the general envelope representation framework, we obtain: \[ l(x) = \inf_{\lambda \geq 0} \left\{ \frac{\lambda}{2}\left( x - \frac{2q-1}{\lambda} \right)^2 - \psi(\lambda) \right\} \, . \] where \(\psi(\lambda) = \frac{\kappa^2}{2\lambda} - \frac{1}{2 \lambda^2}\).

This representation shows how the asymmetric quantile loss can be expressed as an envelope of quadratic functions, connecting it to the Gaussian mixture framework and enabling efficient computational algorithms.

Improper Limit Cases

These expressions lead to three important identities concerning improper limits of GIG and Pólya mixing measures for variance-mean Gaussian mixtures: \[ \begin{aligned} a^{-1} \exp\left\{-2c^{-1} \max(a\theta, 0)\right\} &= \int_0^\infty \phi(\theta \mid -av, cv) dv \\ c^{-1} \exp\left\{-2c^{-1} \rho_q(\theta)\right\} &= \int_0^\infty \phi(\theta \mid -(2\tau - 1)v, cv) e^{-2\tau(1-\tau)v} dv \\ (1 + \exp\{\theta - \mu\})^{-1} &= \int_0^\infty \phi(\theta \mid \mu - \frac{1}{2}v, v) p_{\text{pol}}(v \mid 0, 1) dv \end{aligned} \] where \(\rho_q(\theta) = \frac{1}{2}|\theta| + (q - \frac{1}{2})\theta\) is the check-loss function.

These representations connect to several important regression methods. The first identity relates to Support Vector Machines through the hinge loss in the max function. The second identity connects to Quantile and Lasso Regression via check-loss and \(\ell_1\) penalties. The third identity provides the Logistic Regression representation.

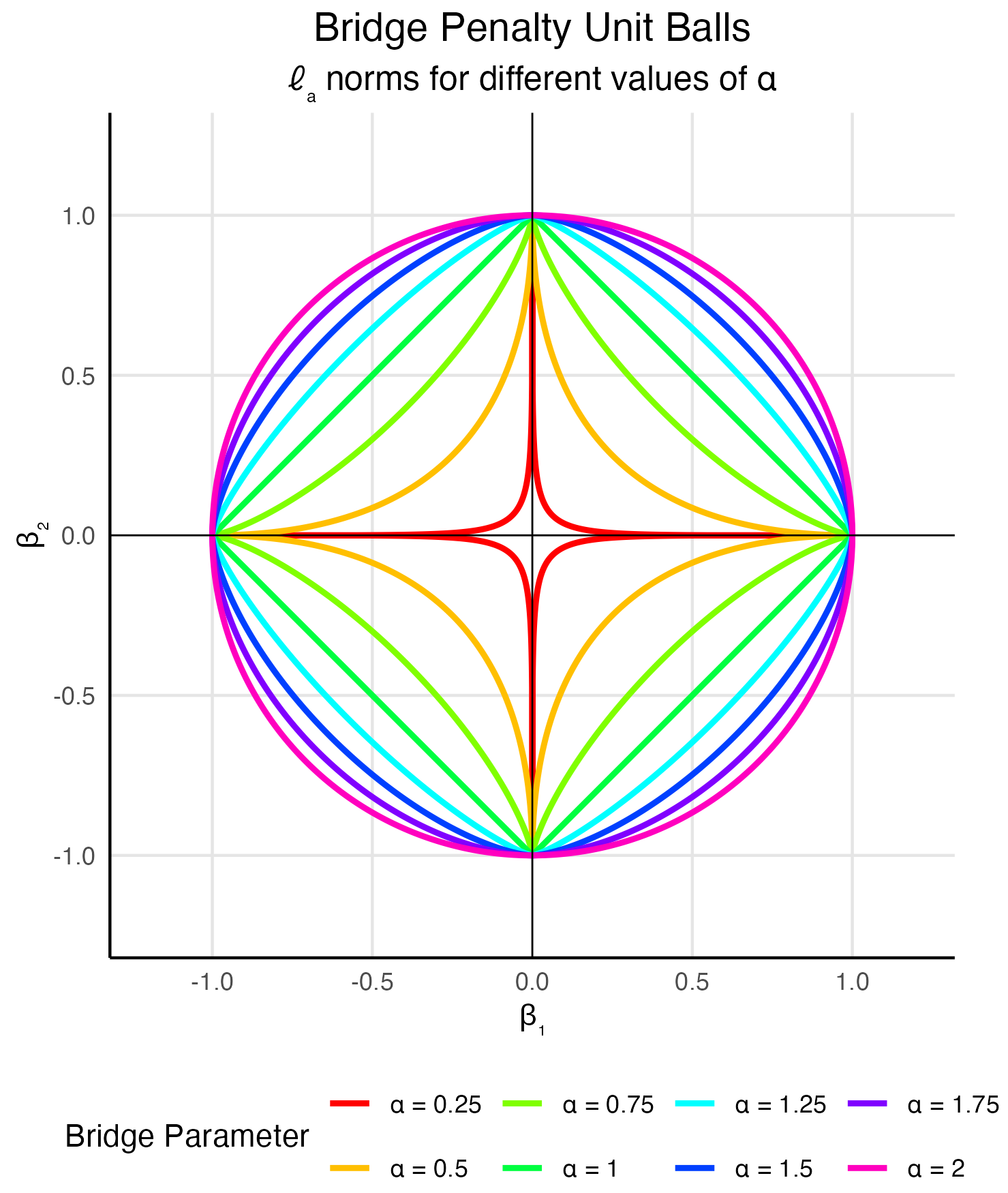

With GIG and Pólya mixing distributions alone, one can generate the following objective functions: \[ \theta^2, \; |\theta|, \; \max(\theta,0), \; \frac{1}{2}|\theta| + (\tau - \frac{1}{2})\theta, \; \frac{1}{1+e^{-\theta}}, \; \frac{1}{(1+e^{-\theta})^r} \]

These correspond to ridge, lasso, support vector machine, check loss/quantile regression, logit, and multinomial models, respectively. More general families can generate other penalty functions—for example, the bridge penalty \(|u|^\alpha\) from a stable mixing distribution.

Computational Advantages

The scale mixture representation provides several computational benefits. Gibbs Sampling becomes efficient because the conditional distributions in the augmented parameter space are often conjugate, enabling tractable MCMC algorithms. EM Algorithms benefit from the E-step involving expectations with respect to the mixing distribution.

This framework has been instrumental in developing efficient algorithms for sparse regression, robust statistics, and non-conjugate Bayesian models. The ability to represent complex penalties as hierarchical Gaussian models bridges the gap between computational tractability and statistical flexibility.

17.9 Lasso Regression (\(\ell_1\) Norm)

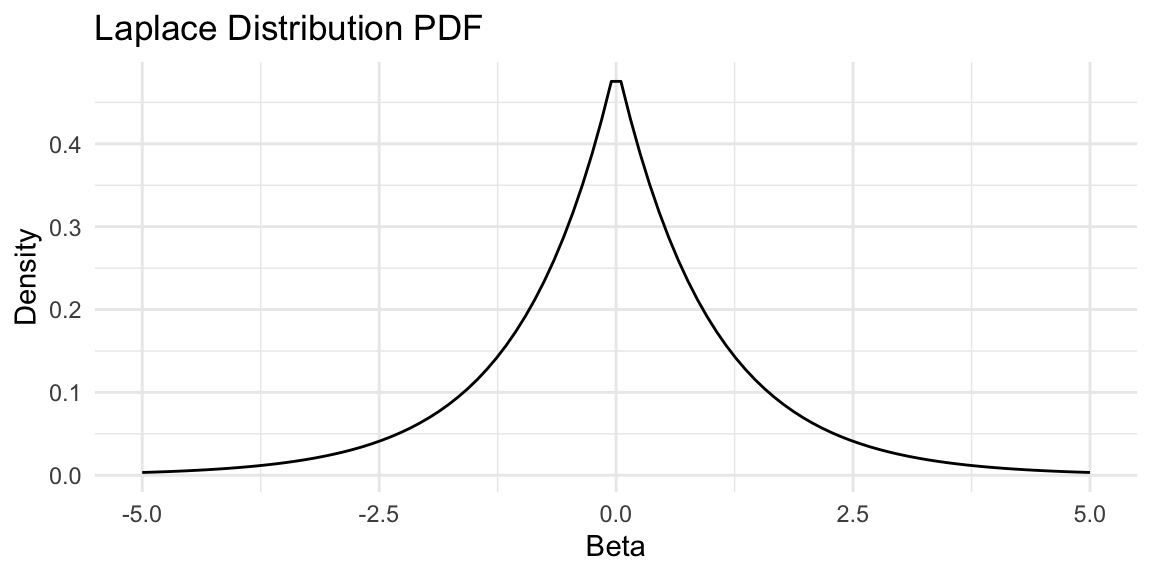

The Lasso (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regression uses a Laplace prior on the parameters of the model \(f\), which leads to an \(\ell_1\) penalty term. Specifically, we assume that the parameters \(\beta\) of the model \(f(x) = x^T\beta\) are distributed as: \[ \beta_j \sim \text{Laplace}(0, b) \quad \text{independently for } j = 1, \ldots, p, \] where \(b > 0\) is the scale parameter. The Laplace distribution has the probability density function: \[ p(\beta_j \mid b) = \frac{1}{2b}\exp\left(-\frac{|\beta_j|}{b}\right) \] and is shown in Figure 17.4.

Code

# PLot Laplace distribution

library(ggplot2)

b <- 1

beta <- seq(-5, 5, length.out = 100)

laplace_pdf <- function(beta, b) {

(1/(2*b)) * exp(-abs(beta)/b)

}

laplace_data <- data.frame(beta = beta, pdf = laplace_pdf(beta, b))

ggplot(laplace_data, aes(x = beta, y = pdf)) +

geom_line() +

labs(title = "", x = "Beta", y = "Density") +

theme_minimal()

The negative log of this prior distribution is given by: \[ -\log p(\beta) = \frac{1}{b} \|\beta\|_1 + \text{const}, \] where \(\|\beta\|_1 = \sum_{j=1}^p |\beta_j|\) is the \(\ell_1\)-norm of the vector \(\beta\). The regularization term \(\phi(f)\) is then given by: \[ \phi(f) = \frac{1}{b} \|\beta\|_1. \] This leads to the following optimization problem: \[ \underset{\beta}{\mathrm{minimize}}\quad \|y- X\beta\|_2^2 + \lambda \|\beta\|_1, \] where \(\lambda = 2\sigma^2/b\) is the regularization parameter that controls the strength of the prior. Unlike ridge regression, the Lasso optimization problem does not have a closed-form solution due to the non-differentiable nature of the \(\ell_1\) penalty. However, efficient algorithms such as coordinate descent and proximal gradient methods can be used to solve it.

The key distinguishing feature of Lasso is its ability to perform automatic variable selection. The \(\ell_1\) penalty encourages sparsity in the coefficient vector \(\hat{\beta}\), meaning that many coefficients will be exactly zero. This property makes Lasso particularly useful for high-dimensional problems where feature selection is important.

When \(\lambda=0\), the Lasso reduces to the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimate. As \(\lambda\) increases, more coefficients are driven to exactly zero, resulting in a sparser model. When \(\lambda\) is very large, all coefficients become zero.

The geometric intuition behind Lasso’s sparsity-inducing property comes from the constraint formulation. We can write the Lasso problem as: \[ \underset{\beta}{\mathrm{minimize}}\quad \|y- X\beta\|_2^2 \quad \text{subject to} \quad \|\beta\|_1 \leq t, \] where \(t\) is a positive constant that controls the sparsity of the solution. The constraint region \(\|\beta\|_1 \leq t\) forms a diamond (in 2D) or rhombus-shaped region with sharp corners at the coordinate axes. The optimal solution often occurs at these corners, where some coefficients are exactly zero.

From a Bayesian perspective, the Lasso estimator corresponds to the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate under independent Laplace priors on the coefficients. We use Bayes rule to calculate the posterior as a product of Normal likelihood and Laplace prior: \[ \log p(\beta \mid y, b) \propto -\|y-X\beta\|_2^2 - \frac{2\sigma^2}{b}\|\beta\|_1. \] For fixed \(\sigma^2\) and \(b>0\), the posterior mode is equivalent to the Lasso estimate with \(\lambda = 2\sigma^2/b\). Large variance \(b\) of the prior is equivalent to small penalty weight \(\lambda\) in the Lasso objective function.

One of the most popular algorithms for solving the Lasso problem is coordinate descent. The algorithm iteratively updates each coefficient while holding all others fixed. For the \(j\)-th coefficient, the update rule is: \[ \hat{\beta}_j \leftarrow \text{soft}\left(\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_{ij}(y_i - \sum_{k \neq j} x_{ik}\hat{\beta}_k), \frac{\lambda}{n}\right), \] where the soft-thresholding operator is defined as: \[ \text{soft}(z, \gamma) = \text{sign}(z)(|z| - \gamma)_+ = \begin{cases} z - \gamma & \text{if } z > \gamma \\ 0 & \text{if } |z| \leq \gamma \\ z + \gamma & \text{if } z < -\gamma \end{cases} \]

Example 17.5 (Sparsity and Variable Selection) We will demonstrate the Lasso’s ability to perform variable selection and shrinkage using simulated data. The data will consist of a design matrix with correlated predictors and a sparse signal, where only a 5 out of 20 predictors have non-zero coefficients.

Code

# Generate simulated data

set.seed(123)

n <- 100 # number of observations

p <- 20 # number of predictors

sigma <- 1 # noise level

# Create design matrix with some correlation structure

X <- matrix(rnorm(n * p), n, p)

# Add some correlation between predictors

for(i in 2:p) {

X[, i] <- 0.5 * X[, i-1] + sqrt(0.75) * X[, i]

}# True coefficients - sparse signal

beta_true <- c(3, -2, 1.5, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, -1, rep(0, 10))

sparse_indices <- which(beta_true != 0)

# Generate response

y <- X %*% beta_true + sigma * rnorm(n)Then we use glmnet package to fit the Lasso model and visualize the coefficient paths. We will also perform cross-validation to select the optimal regularization parameter \(\lambda\).

# Fit LASSO path using glmnet

library(glmnet)

lasso_fit <- glmnet(X, y, alpha = 1)

# Plot coefficient paths

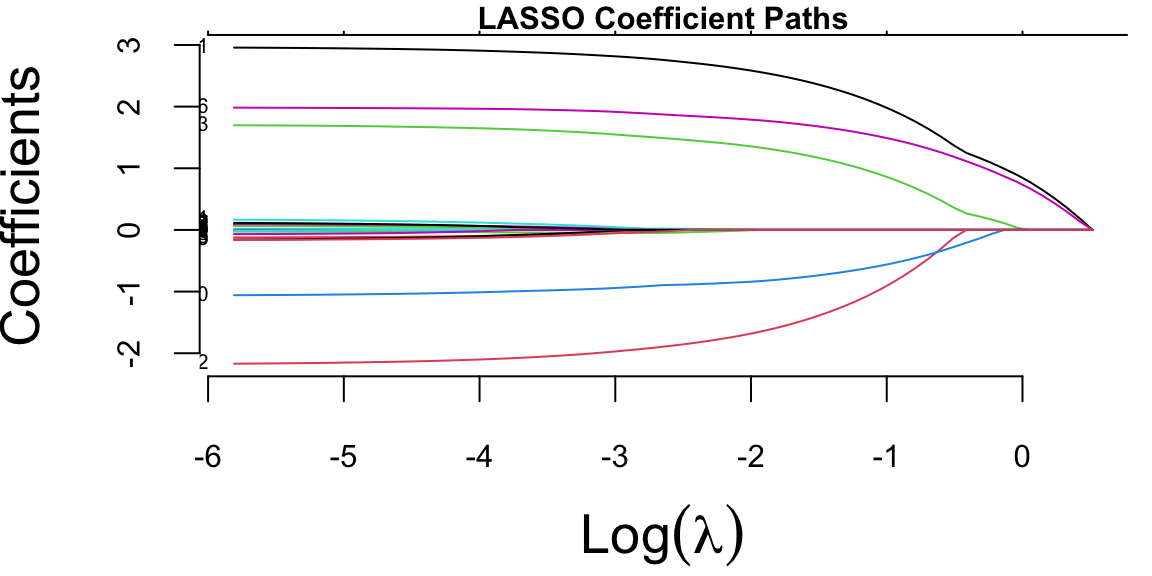

plot(lasso_fit, xvar = "lambda", label = TRUE)

The coefficient paths plot shows how LASSO coefficients shrink toward zero as the regularization parameter lambda increases. The colored lines represent different predictors, demonstrating LASSO’s variable selection property. Note, that glmnet fitted the model for a sequence of \(\lambda\) values. The algorithms starts with a large lambda value, where all coefficients are penalized to zero. Then, it gradually decreases lambda, using the coefficients from the previous, slightly more penalized model as a “warm start” for the current calculation. This pathwise approach is significantly more efficient than starting the optimization from scratch for every single \(\lambda\). By default, glmnet computes the coefficients for a sequence of 100 lambda values spaced evenly on the logarithmic scale, starting from a data-driven maximum value (where all coefficients are zero) down to a small fraction of that maximum. The user can specify their own sequence of lambda values if specific granularity or range is desired

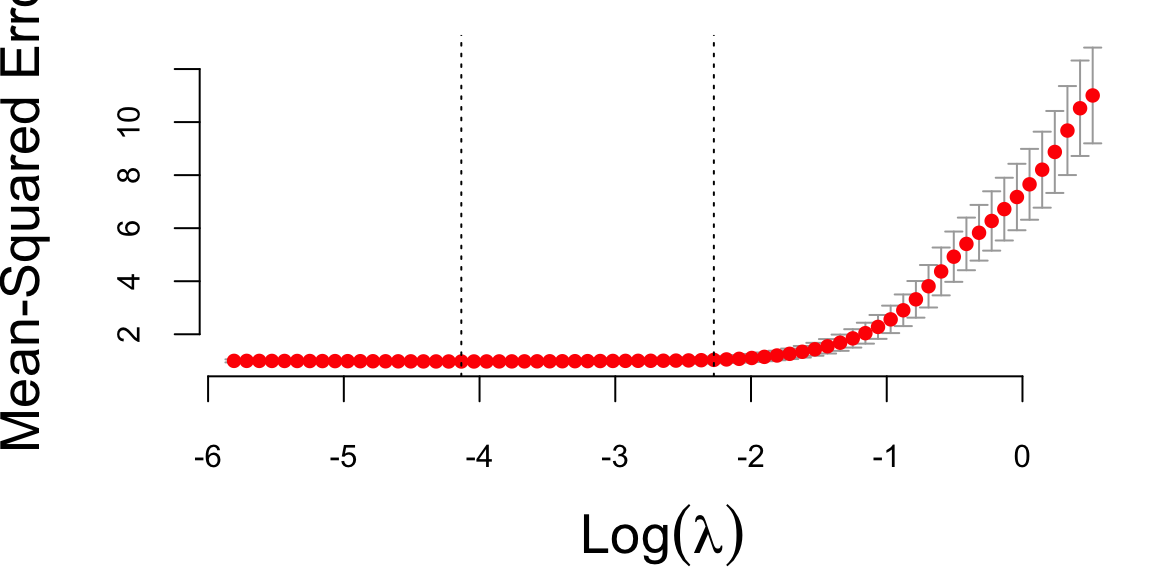

Finally, we will perform cross-validation to select the optimal \(\lambda\) value and compare the estimated coefficients with the true values.

# Cross-validation to select optimal lambda

cv_lasso <- cv.glmnet(X, y, alpha = 1, nfolds = 10)

# Plot cross-validation curve

plot(cv_lasso)

Now, we can extract the coefficients lambda.min and lambda.1se from the cross-validation results, which correspond to the minimum cross-validated error and the most regularized model within one standard error of the minimum, respectively.

# Extract coefficients at optimal lambda

lambda_min <- cv_lasso$lambda.min

lambda_1se <- cv_lasso$lambda.1se

coef_min <- coef(lasso_fit, s = lambda_min)

coef_1se <- coef(lasso_fit, s = lambda_1se)

# Print values of lambda

cat("Optimal lambda (min):", lambda_min, "\n")

## Optimal lambda (min): 0.016

cat("Optimal lambda (1se):", lambda_1se, "\n")

## Optimal lambda (1se): 0.1Code

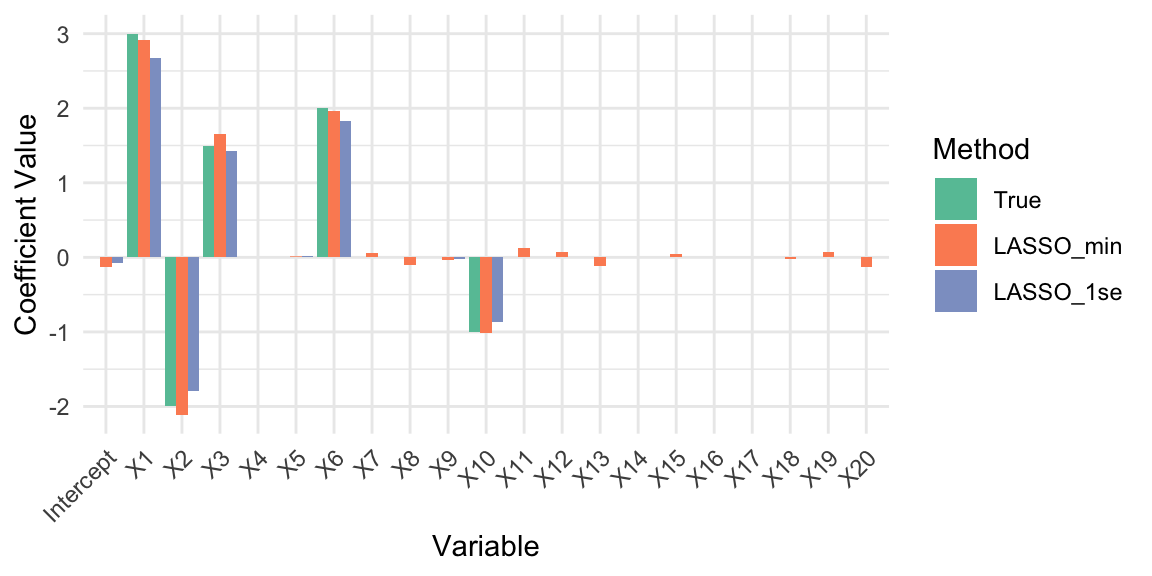

# Compare estimates with true values

comparison <- data.frame(

True = c(0, beta_true), # Include intercept

LASSO_min = as.vector(coef_min),

LASSO_1se = as.vector(coef_1se)

)

rownames(comparison) <- c("Intercept", paste0("X", 1:p))

# Visualization of coefficient estimates

library(reshape2)

library(ggplot2)

# Melt data for plotting

plot_data <- melt(comparison, id.vars = NULL)

plot_data$Variable <- rep(rownames(comparison), 3)

plot_data$Variable <- factor(plot_data$Variable, levels = rownames(comparison))

ggplot(plot_data, aes(x = Variable, y = value, fill = variable)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity", position = "dodge") +

theme_minimal() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1)) +

labs(y = "Coefficient Value", fill = "Method") +

scale_fill_brewer(type = "qual", palette = "Set2")

It seems like LASSO has successfully identified the non-zero coefficients and shrunk the noise variables to zero. The coefficient estimates at lambda.min and lambda.1se show that LASSO retains the true signals while effectively ignoring the noise. Let’s calculate the prediction errors and evaluate the variable selection performance of LASSO at both optimal \(\lambda\) values.

# Calculate prediction errors

pred_min <- predict(lasso_fit, newx = X, s = lambda_min)

pred_1se <- predict(lasso_fit, newx = X, s = lambda_1se)

mse_min <- mean((y - pred_min)^2)

mse_1se <- mean((y - pred_1se)^2)

cat("Mean Squared Error (lambda.min):", round(mse_min, 3), "\n")

## Mean Squared Error (lambda.min): 0.68

cat("Mean Squared Error (lambda.1se):", round(mse_1se, 3), "\n")

## Mean Squared Error (lambda.1se): 0.85In summary, this example demonstrates how LASSO regression can be used for both variable selection and regularization in high-dimensional settings. By tuning the regularization parameter \(\lambda\), LASSO is able to shrink irrelevant coefficients to zero, effectively identifying the true underlying predictors while controlling model complexity. The comparison of coefficient estimates and prediction errors at different \(\lambda\) values highlights the trade-off between model sparsity and predictive accuracy. LASSO’s ability to produce interpretable, sparse models makes it a powerful tool in modern statistical learning, especially when dealing with datasets where the number of predictors may be large relative to the number of observations.

Scale Mixture Representation

The Laplace distribution can be represented as a scale mixture of Normal distributions (Andrews and Mallows 1974): \[ \begin{aligned} \beta_j \mid \sigma^2,\tau_j &\sim N(0,\tau_j^2\sigma^2)\\ \tau_j^2 \mid \alpha &\sim \text{Exp}(\alpha^2/2)\\ \sigma^2 &\sim \pi(\sigma^2). \end{aligned} \] We can show equivalence by integrating out \(\tau_j\): \[ p(\beta_j\mid \sigma^2,\alpha) = \int_{0}^{\infty} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \tau_j\sigma^2}}\exp\left(-\frac{\beta_j^2}{2\sigma^2\tau_j^2}\right)\frac{\alpha^2}{2}\exp\left(-\frac{\alpha^2\tau_j^2}{2}\right)d\tau_j = \frac{\alpha}{2\sigma}\exp\left(-\frac{\alpha|\beta_j|}{\sigma}\right). \] Thus it is a Laplace distribution with location 0 and scale \(\alpha/\sigma\). Representation of Laplace prior is a scale Normal mixture allows us to apply an efficient numerical algorithm for computing samples from the posterior distribution. This algorithms is called a Gibbs sample and it iteratively samples from \(\theta \mid a,y\) and \(b\mid \theta,y\) to estimate joint distribution over \((\hat \theta, \hat b)\). Thus, we so not need to apply cross-validation to find optimal value of \(b\), the Bayesian algorithm does it “automatically”.

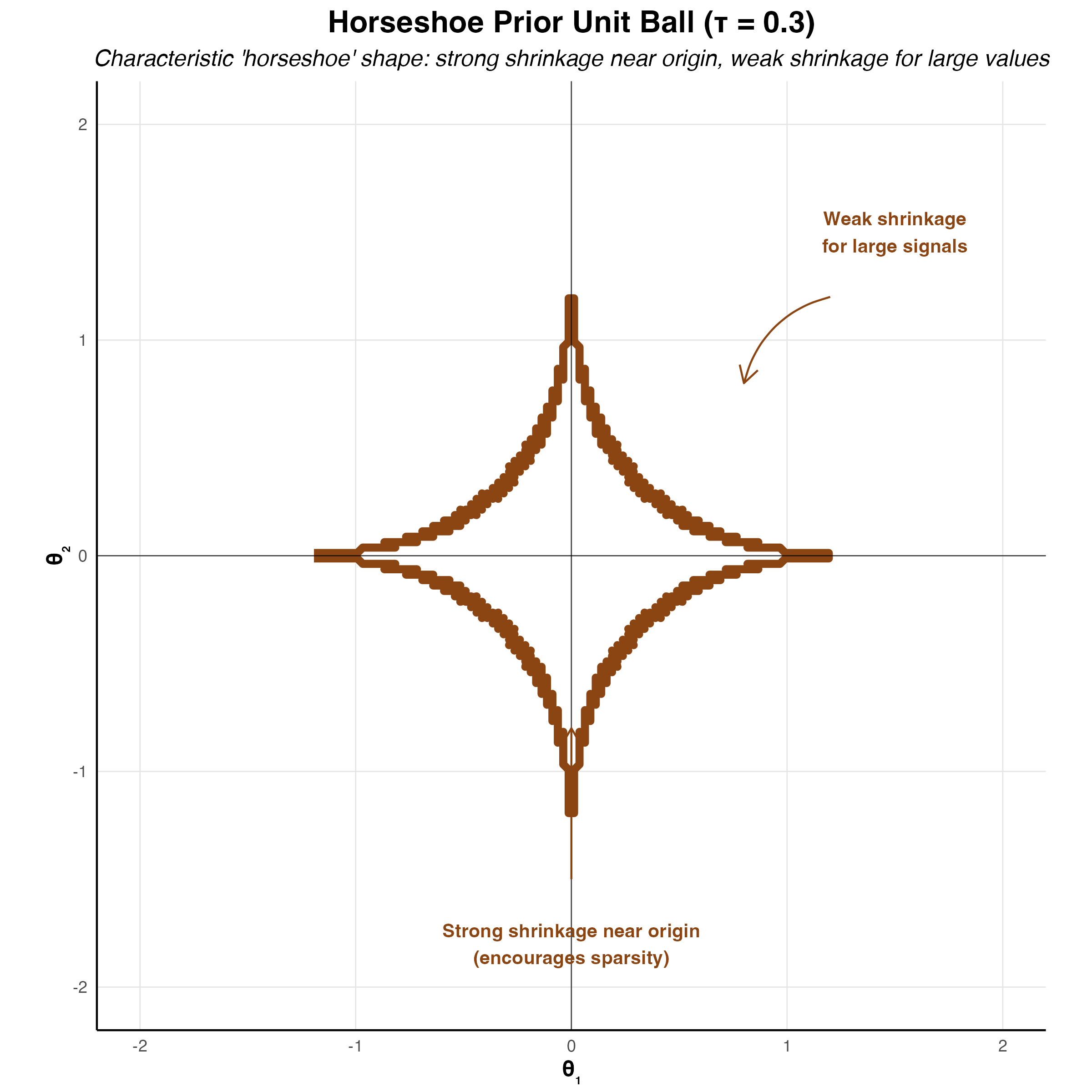

17.10 Horseshoe

The horseshoe prior represents a significant advancement in Bayesian sparse estimation, addressing fundamental limitations of the Lasso while maintaining computational tractability (Carvalho, Polson, and Scott 2010). The name derives from the shape of its shrinkage profile, which resembles an inverted horseshoe: it applies minimal shrinkage to large signals while aggressively shrinking noise coefficients toward zero. This behavior makes it particularly attractive for high-dimensional problems where strong sparsity is expected but we want to avoid over-shrinking the true signals.

Unlike the Lasso, which applies constant shrinkage across all coefficient magnitudes, the horseshoe exhibits adaptive shrinkage. Small coefficients receive heavy regularization approaching zero, while large coefficients are left nearly unregularized. This is precisely the behavior we desire in sparse estimation: confidently shrink noise to zero while preserving signal fidelity. The horseshoe achieves this through a hierarchical Bayesian structure that places a half-Cauchy prior on local scale parameters.

Mathematical Formulation

The horseshoe prior is defined through a hierarchical scale mixture of normals. For the regression model \(y = X\beta + \epsilon\) with \(\epsilon \sim N(0, \sigma^2 I)\), the horseshoe prior on coefficients \(\beta_j\) is specified as:

\[ \begin{aligned} \beta_j \mid \lambda_j, \tau, \sigma^2 &\sim N(0, \lambda_j^2 \tau^2 \sigma^2) \\ \lambda_j &\sim \text{Cauchy}^+(0, 1) \\ \tau &\sim \text{Cauchy}^+(0, 1) \end{aligned} \tag{17.5}\]

where \(\text{Cauchy}^+(0, 1)\) denotes the half-Cauchy distribution (the positive half of a standard Cauchy). The parameter \(\lambda_j\) is the local shrinkage parameter for coefficient \(\beta_j\), while \(\tau\) is the global shrinkage parameter that controls overall sparsity. The product \(\kappa_j = \lambda_j \tau\) determines the effective scale of \(\beta_j\).

The half-Cauchy distribution can be represented as a scale mixture itself:

\[ \lambda_j \sim \text{Cauchy}^+(0, 1) \iff \lambda_j^2 \mid \nu_j \sim \text{Inv-Gamma}(1/2, 1/\nu_j), \quad \nu_j \sim \text{Inv-Gamma}(1/2, 1) \]

This hierarchical representation enables efficient Gibbs sampling for posterior inference, as each conditional distribution has a closed form.

Shrinkage Properties

The horseshoe prior induces a shrinkage factor \(\kappa_j(\beta_j) = E[\kappa_j \mid \beta_j, y]\) that adapts to the data. For large coefficient values \(|\beta_j|\), the shrinkage factor approaches 1 (no shrinkage), while for small values it approaches 0 (complete shrinkage). This can be seen through the marginal prior:

\[ p(\beta_j \mid \tau, \sigma^2) = \int_0^{\infty} N(\beta_j \mid 0, \lambda_j^2 \tau^2 \sigma^2) \cdot \text{Cauchy}^+(\lambda_j \mid 0, 1) d\lambda_j \]

The resulting marginal distribution has extremely heavy tails compared to the Laplace prior used in Lasso. Specifically, the horseshoe has infinite moments, while the Laplace has exponential tails. This heavy-tailed behavior means that large signals are barely regularized, avoiding the systematic bias inherent in \(\ell_1\) penalties.

The posterior mean under the horseshoe prior can be approximated as:

\[ E[\beta_j \mid y] \approx (1 - \kappa_j) \cdot 0 + \kappa_j \cdot \hat{\beta}_j^{\text{OLS}} \]

where \(\hat{\beta}_j^{\text{OLS}}\) is the ordinary least squares estimate and \(\kappa_j \in (0,1)\) is the data-dependent shrinkage factor. Unlike Lasso, where the shrinkage is constant across coefficients, \(\kappa_j\) adapts to the observed magnitude of \(\hat{\beta}_j^{\text{OLS}}\).

Comparison with Other Priors

The horseshoe prior occupies a distinctive position in the landscape of sparse priors. Consider the shrinkage behavior as a function of the observed coefficient:

- Ridge (\(\ell_2\)): Shrinkage factor \(\kappa_j = 1/(1 + \lambda)\) is constant, providing uniform shrinkage regardless of signal strength

- Lasso (\(\ell_1\)): Shrinkage is constant for small coefficients and linear for large ones, \(\kappa_j \approx 1 - \lambda/|\beta_j|\) for large \(|\beta_j|\)

- Horseshoe: Shrinkage factor varies from 0 for noise to nearly 1 for signals, \(\kappa_j \approx (\lambda_j^2 \tau^2)/(\lambda_j^2 \tau^2 + \sigma^2)\)

The global-local structure separates two tasks: \(\tau\) determines how many coefficients should be non-zero (controlling overall sparsity), while each \(\lambda_j\) determines whether its specific coefficient belongs to the signal or noise group. This separation leads to superior performance in recovering sparse signals compared to the Lasso, particularly when true coefficients vary substantially in magnitude.

Computational Implementation

The horseshoe prior admits efficient posterior sampling through Gibbs sampling, leveraging its hierarchical structure. The full conditional distributions are:

\[ \begin{aligned} (\beta \mid y, \lambda, \tau, \sigma^2) &\sim N\left((X'X + D_\lambda^{-1})^{-1}X'y, \sigma^2(X'X + D_\lambda^{-1})^{-1}\right) \\ (\sigma^2 \mid y, \beta) &\sim \text{Inv-Gamma}\left(\frac{n}{2}, \frac{1}{2}\|y - X\beta\|^2\right) \\ (\lambda_j^2 \mid \beta_j, \tau, \sigma^2, \nu_j) &\sim \text{Inv-Gamma}\left(1, \frac{1}{\nu_j} + \frac{\beta_j^2}{2\tau^2\sigma^2}\right) \\ (\tau^2 \mid \beta, \lambda, \sigma^2, \xi) &\sim \text{Inv-Gamma}\left(\frac{p+1}{2}, \frac{1}{\xi} + \frac{1}{2\sigma^2}\sum_{j=1}^p \frac{\beta_j^2}{\lambda_j^2}\right) \end{aligned} \]

where \(D_\lambda = \text{diag}(\lambda_1^2\tau^2, \ldots, \lambda_p^2\tau^2)\) and \(\nu_j, \xi\) are auxiliary variables from the scale mixture representation of the half-Cauchy.

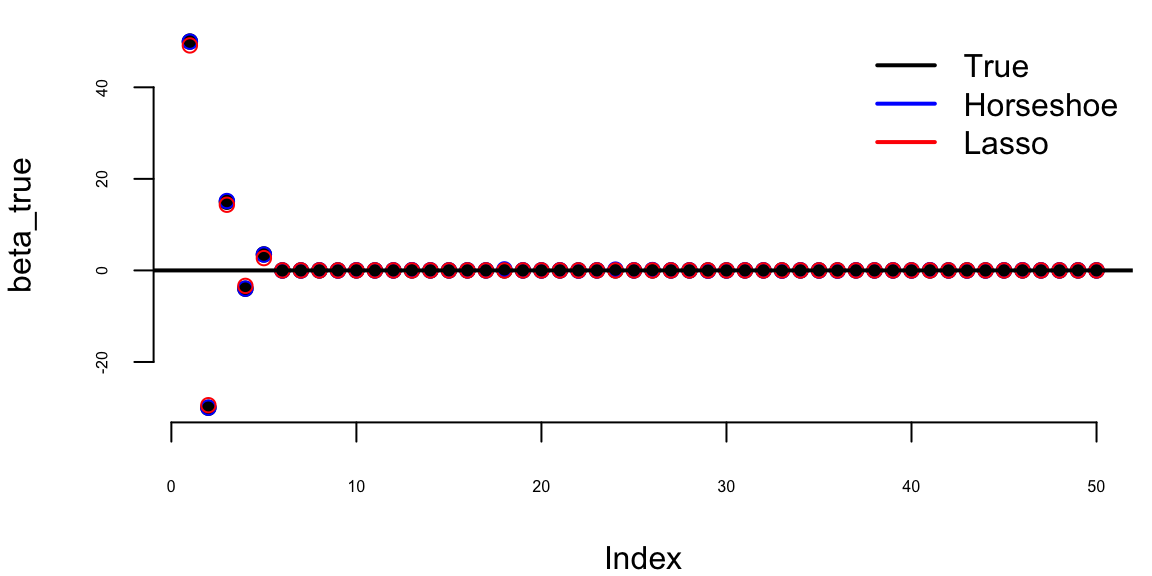

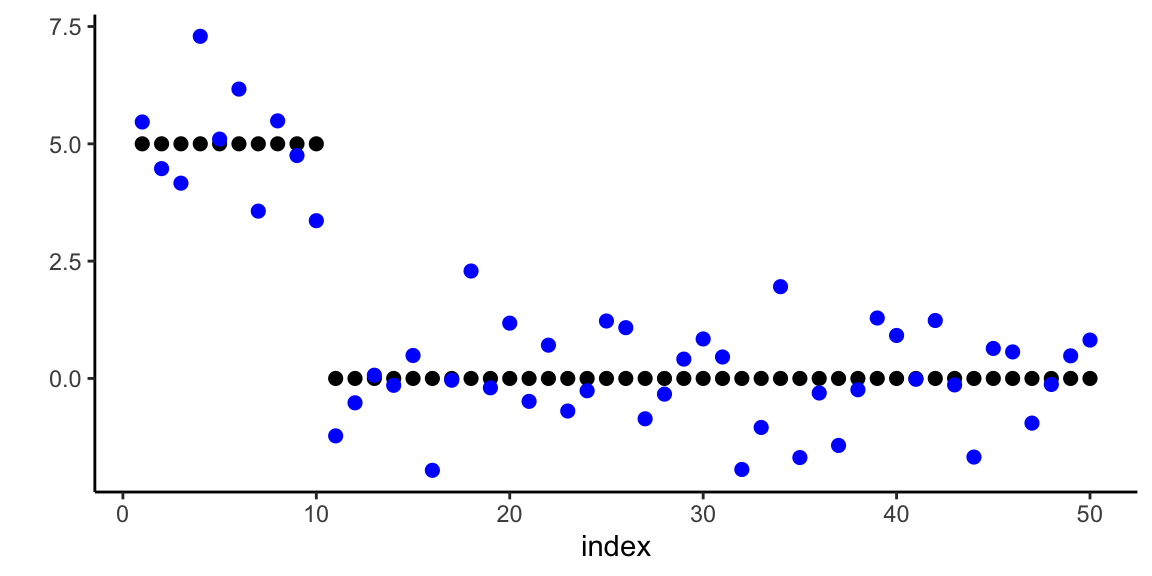

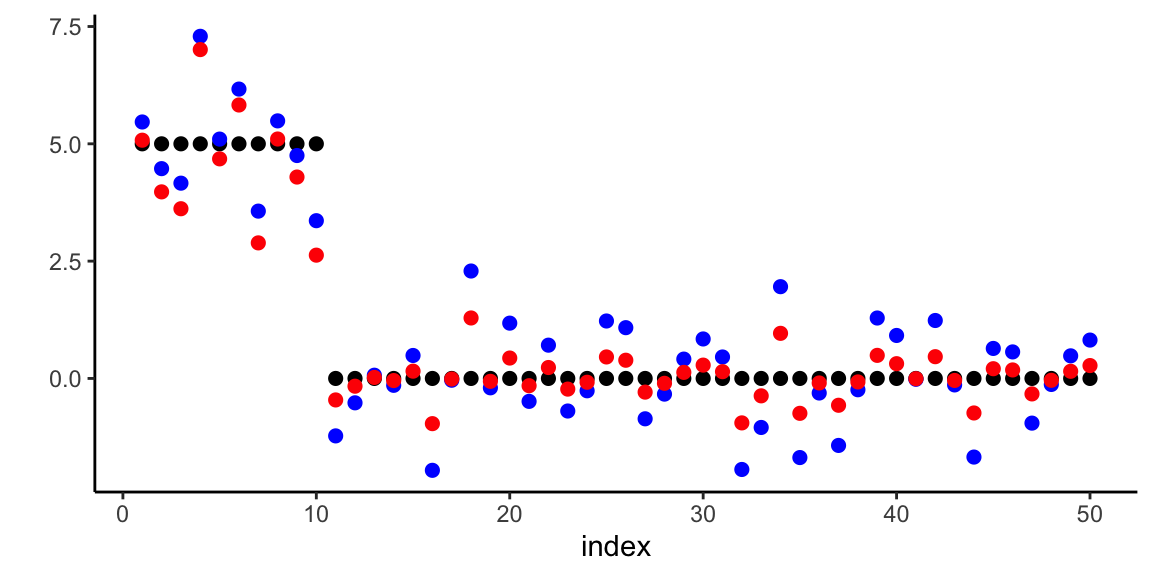

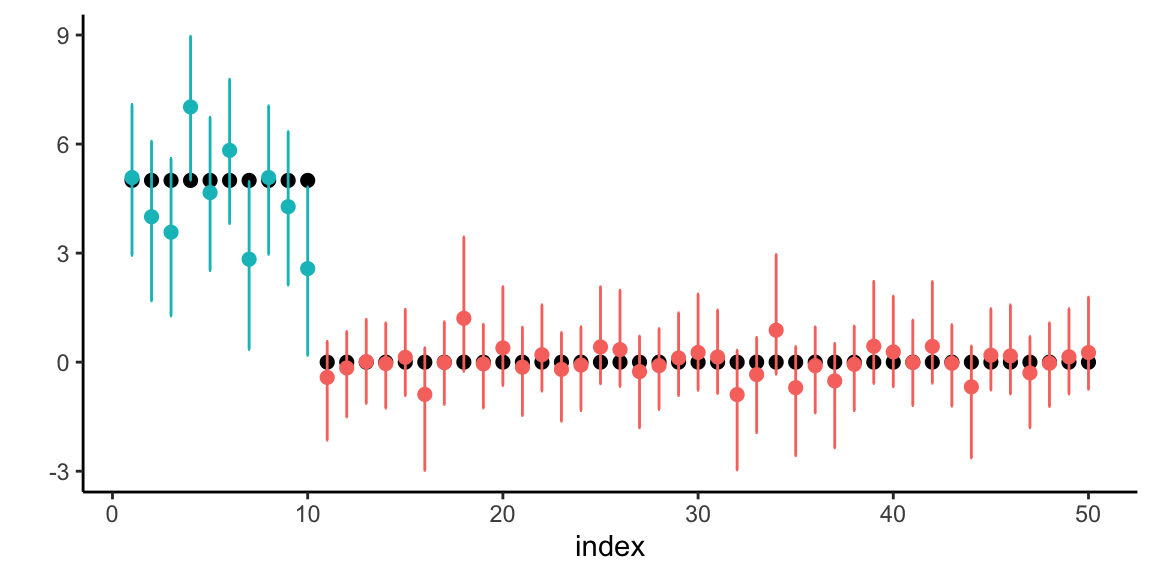

Example 17.6 (Horseshoe Prior for Sparse Regression) We demonstrate the horseshoe prior’s ability to recover sparse signals in a high-dimensional regression setting. Consider a scenario with \(n = 100\) observations and \(p = 50\) predictors, where only 5 coefficients are truly non-zero with varying magnitudes.

Horseshoe Prior for Sparse Regression

#| warning: false

#| message: false

# Set seed for reproducibility

set.seed(123)

# Generate sparse regression data

n <- 100 # number of observations

p <- 50 # number of predictors

s <- 5 # number of non-zero coefficients

# True sparse coefficient vector

beta_true <- rep(0, p)

beta_true[1:s] <- c(50, -30, 15, -4, 3.5) # Varying magnitudes

# Generate design matrix (standardized)

X <- matrix(rnorm(n * p), n, p)

X <- scale(X)

# Generate response with noise

sigma_true <- 1

y <- X %*% beta_true + rnorm(n, 0, sigma_true)

y <- as.vector(y)

# Horseshoe Gibbs sampler

horseshoe_gibbs <- function(y, X, n_iter = 5000, burn_in = 1000) {

n <- nrow(X)

p <- ncol(X)

# Initialize parameters

beta <- rep(0, p)

lambda_sq <- rep(1, p)

tau_sq <- 1

sigma_sq <- 1

nu <- rep(1, p)

xi <- 1

# Storage for samples

beta_samples <- matrix(0, n_iter - burn_in, p)

tau_sq_samples <- numeric(n_iter - burn_in)

# Pre-compute X'X and X'y

XtX <- crossprod(X)

Xty <- crossprod(X, y)

for (iter in 1:n_iter) {

# Sample beta from full conditional

D_lambda_inv <- diag(1 / (lambda_sq * tau_sq))

V_beta <- solve(XtX + D_lambda_inv)

mu_beta <- V_beta %*% Xty

beta <- mu_beta + t(chol(sigma_sq * V_beta)) %*% rnorm(p)

# Sample sigma^2

resid <- y - X %*% beta

sigma_sq <- 1 / rgamma(1, n/2, sum(resid^2)/2)

# Sample lambda_j^2 for each j

for (j in 1:p) {

lambda_sq[j] <- 1 / rgamma(1, 1, 1/nu[j] + beta[j]^2/(2*tau_sq*sigma_sq))

}

# Sample nu_j (auxiliary for half-Cauchy)

for (j in 1:p) {

nu[j] <- 1 / rgamma(1, 1, 1 + 1/lambda_sq[j])

}

# Sample tau^2 (global shrinkage)

tau_sq <- 1 / rgamma(1, (p+1)/2, 1/xi + sum(beta^2/lambda_sq)/(2*sigma_sq))

# Sample xi (auxiliary for tau)

xi <- 1 / rgamma(1, 1, 1 + 1/tau_sq)

# Store samples after burn-in

if (iter > burn_in) {

beta_samples[iter - burn_in, ] <- beta

tau_sq_samples[iter - burn_in] <- tau_sq

}

}

list(beta = beta_samples, tau_sq = tau_sq_samples)

}Fit Horseshoe model

hs_fit <- horseshoe_gibbs(y, X, n_iter = 5000, burn_in = 1000)

# Compute posterior means

beta_hs <- colMeans(hs_fit$beta)

tau_hs <- mean(hs_fit$tau_sq)

# Compare with Lasso

library(glmnet)

lasso_fit <- cv.glmnet(X, y, alpha = 1)

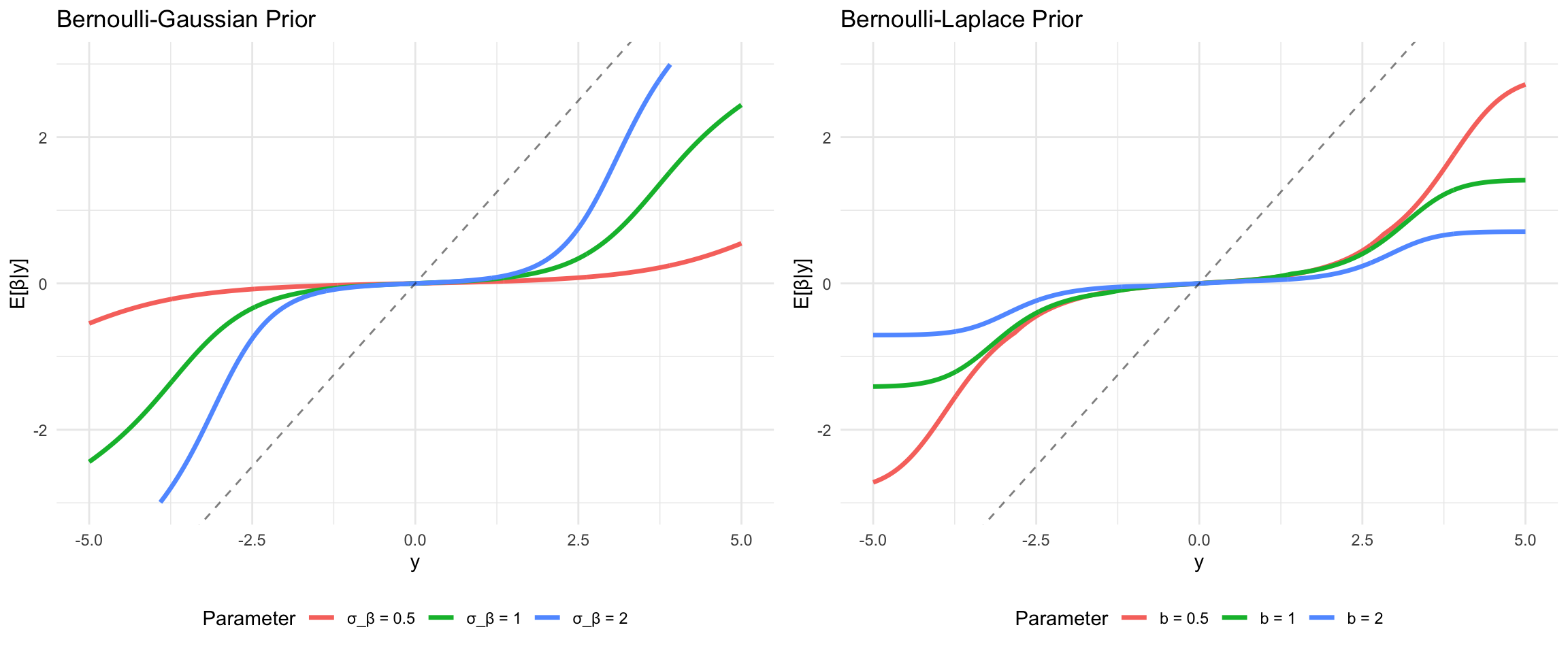

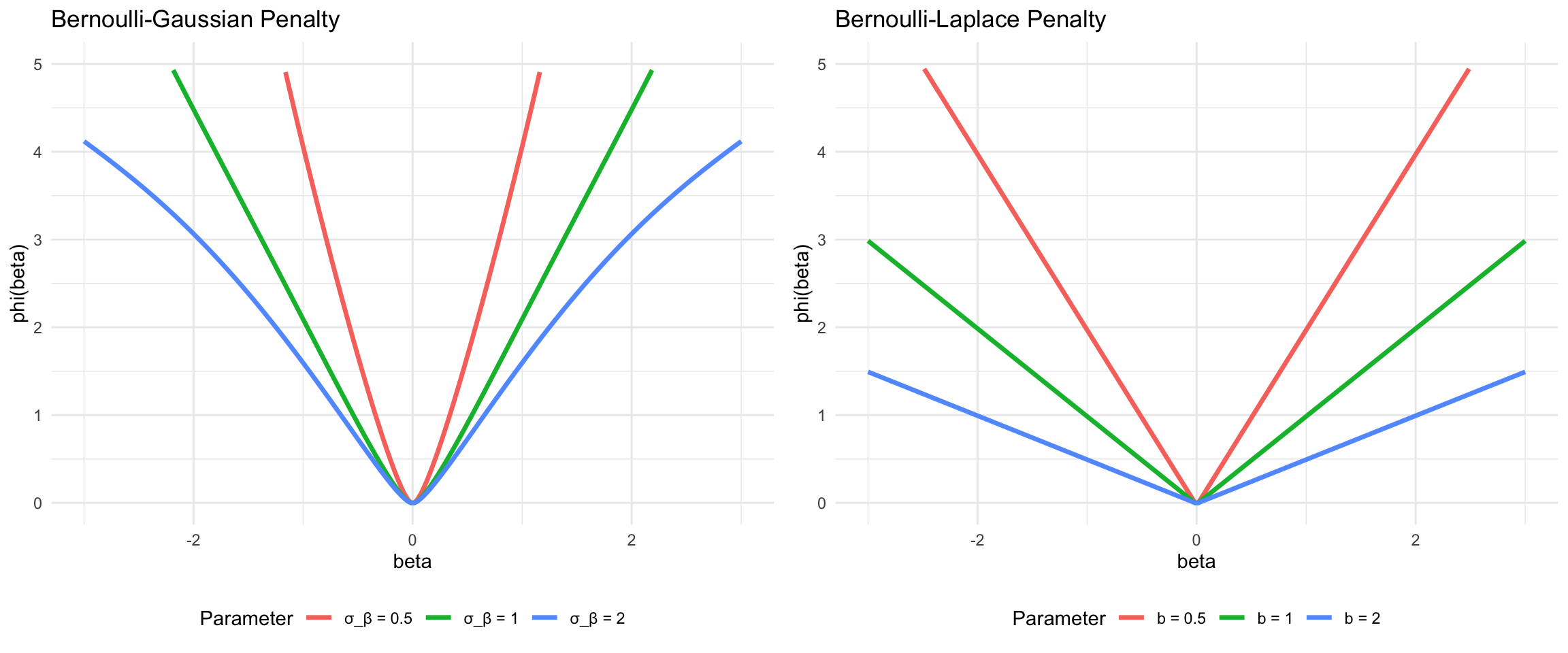

beta_lasso <- as.vector(coef(lasso_fit, s = "lambda.min"))[-1]