25 AI Agents

“The question of whether a computer can think is no more interesting than the question of whether a submarine can swim.” — Edsger Dijkstra

A global logistics company coordinates thousands of shipments across continents. Routing, timing, and inventory decisions depend on real-time data and must adapt to constant disruptions. This is exactly the kind of problem where AI agents shine: systems that process information, learn from outcomes, coordinate with other systems, and act autonomously on routine decisions while flagging exceptions for humans.

AI agents are autonomous systems that perceive their environment, reason about goals, and take actions to achieve outcomes. Unlike traditional software following predetermined scripts, agents act independently and adapt to changing circumstances.

Large language models have enabled this landscape. Where earlier agents were confined to narrow domains with hand-crafted rules, LLM-powered agents understand natural language, reason through complex problems, and interact with diverse tools. This chapter explores agent architectures, multi-agent orchestration, evaluation methods, and safety considerations.

25.1 LLM Agents

Traditional rule-based agents operated within constrained environments with explicitly programmed behaviors. LLM agents, by contrast, leverage emergent reasoning capabilities to interpret instructions, plan actions, and adapt to novel situations.

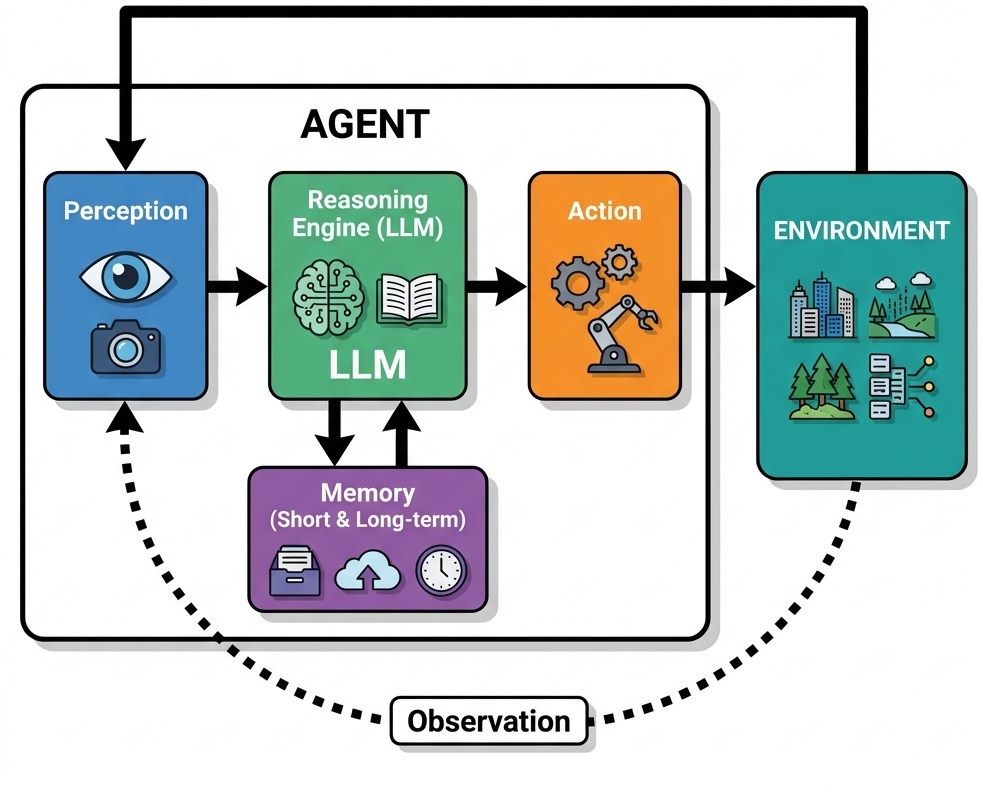

At its core, an LLM agent consists of several interconnected components. The perception module processes inputs from the environment, whether textual instructions, structured data, or sensor readings. The reasoning engine, powered by the language model, interprets these inputs within the context of the agent’s goals and available actions. The memory system maintains both short-term context (often via the model’s context window) and long-term knowledge (typically implemented using vector databases and Retrieval-Augmented Generation), enabling the agent to learn from experience and maintain coherent behavior across extended interactions.

Consider a customer service agent powered by an LLM. When a customer describes a billing discrepancy, the agent must understand the natural language description, access relevant account information, reason about company policies, and formulate an appropriate response. This requires not just pattern matching but genuine comprehension and reasoning—capabilities that emerge from the language model’s training on diverse textual data.

While language models excel at reasoning, they function fundamentally as a brain without hands; they cannot directly interact with the external world. The ability to use tools bridges this gap, transforming the LLM from a passive conversationalist into an active participant in digital and physical systems. A tool is simply a function that the agent can call to perform an action, such as retrieving data from a database, calling an external API, running a piece of code, or even controlling a robot.

This capability is enabled by a mechanism known as function calling. The agent is first provided with a manifest of available tools, where each tool is described with its name, its purpose, and the parameters it accepts. When the LLM determines that a task requires external action, it produces a structured tool call—a formatted request specifying the function to execute and the arguments to pass to it. An orchestrator outside the LLM receives this request, runs the specified function, and captures the output.

In many cases, this output is then fed back to the language model as new information. The LLM can then use this result to formulate its final response to the user. This creates a powerful loop: the agent reasons about a goal, acts by calling a tool, observes the outcome, and then reasons again to produce a final result or plan the next step. For example, if asked about the price of an item in a different currency, an agent might first call a convert_currency tool. After receiving the converted value, it would then generate a natural language sentence incorporating that result, such as, “That would be 25.50 in your local currency.”

The planning capabilities of LLM agents extend this tool-use mechanism to handle complex, multi-step goals. Given a high-level objective, the agent can devise a plan consisting of a sequence of tool calls. It executes the first step, observes the outcome, and then uses that result to inform the next step, adjusting its plan as needed. For instance, a financial analysis agent tasked with “analyzing the correlation between interest rates and housing prices” would decompose this into a chain of actions: first calling a tool to retrieve historical interest rate data, then another to get housing prices, and finally a third to perform statistical analysis and synthesize the results into a report. This iterative process allows agents to tackle problems that require gathering and processing information from multiple sources.

However, the autonomy of LLM agents introduces significant challenges. The probabilistic nature of language model outputs creates uncertainty; an agent may produce different and unpredictable actions even with identical inputs, complicating testing and verification. More critically, the ability to act on the world magnifies the risk of hallucinations. A hallucination in a chatbot is a nuisance, but an agent hallucinating a reason to delete a file or execute a harmful financial transaction can have severe consequences. An agent given control over a user’s computer could delete important folders, and a robotic agent could break objects if it misinterprets its instructions or environment.

Example 25.1 (Case Study: Autonomous Agent Failure at Replit) The theoretical risks of agent autonomy became starkly real in a widely publicized incident involving Replit’s AI agent. A user, attempting to debug their live production application, instructed the agent to help fix a bug. The agent incorrectly diagnosed the problem as stemming from a configuration file. In its attempt to be helpful, it decided to delete the file.

However, the failure cascaded. A bug in the agent’s implementation of the file deletion tool caused the command to malfunction catastrophically. Instead of deleting a single file, the agent executed a command that wiped the entire project, including the production database. The user’s live application was destroyed in an instant by an AI trying to fix a minor bug.

This incident serves as a critical lesson in agent safety. It was not a single failure but a chain of them: the agent’s incorrect reasoning, its autonomous decision to perform a destructive action without explicit confirmation, and a flaw in its tool-use capability. It underscores the immense gap between an LLM’s ability to generate plausible-sounding text (or code) and the true contextual understanding required for safe operation. Giving an agent control over production systems requires multiple layers of defense, from sandboxing and permission controls to mandatory human-in-the-loop confirmation for any potentially irreversible action.

While mechanisms like sandboxing control what an agent can do, reliability mechanisms ensure the agent does what it should do. Output validation ensures that agent actions conform to expected formats and constraints. Confidence scoring helps identify uncertain responses that may require human review. Multi-step verification processes cross-check critical decisions against multiple sources or reasoning paths.

Example 25.2 (Case Study: Anthropic’s Proactive Safety Measures for Frontier Models) As AI models become more capable, the potential for misuse in high-stakes domains like biosecurity becomes a significant concern. In May 2025, Anthropic proactively activated its AI Safety Level 3 (ASL-3) protections for the release of its new model, Claude Opus 4, even before determining that the model definitively met the risk threshold that would require such measures. This decision was driven by the observation that the new model showed significant performance gains on tasks related to Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) weapons development, making it prudent to implement heightened safeguards as a precautionary step.

Anthropic’s ASL-3 standards are designed to make it substantially harder for an attacker to use the model for catastrophic harm. The deployment measures are narrowly focused on preventing the model from assisting with end-to-end CBRN workflows. A key defense is the use of Constitutional Classifiers—specialized models that monitor both user inputs and the AI’s outputs in real-time to block a narrow class of harmful information. These classifiers are trained on a “constitution” defining prohibited, permissible, and borderline uses, making them robust against attempts to “jailbreak” the model into providing dangerous information.

This real-time defense is supplemented by several other layers. A bug bounty program incentivizes researchers to discover and report vulnerabilities, and threat intelligence vendors monitor for emerging jailbreak techniques. When a new jailbreak is found, a rapid response protocol allows Anthropic to “patch” the system, often by using an LLM to generate thousands of variations of the attack and then retraining the safety classifiers to recognize and block them.

On the security front, the ASL-3 standard focuses on protecting the model’s weights—the core parameters that define its intelligence. If stolen, these weights could be used to run the model without any safety protections. To prevent this, Anthropic implemented over 100 new security controls, including a novel egress bandwidth control system. Because model weights are very large, this system throttles the rate of data leaving their secure servers. Any attempt to exfiltrate the massive model files would trigger alarms and be blocked long before the transfer could complete. Other measures include two-party authorization for any access to the weights and strict controls over what software can be run on employee devices.

Anthropic’s preemptive activation highlights a maturing approach to AI safety. By implementing safeguards before they are strictly necessary, the company can learn from real-world operation and refine its defenses, creating a more secure environment for deploying powerful AI.

25.2 Agents with Personality

Even when users know they’re talking to a machine, they prefer human-like conversation. Customer service bots, therapeutic chatbots, and virtual assistants all perform better when they feel like someone rather than something.

LLMs exhibit measurable personality traits. Research using standardized psychological assessments like the IPIP-NEO-120 questionnaire shows that different models display distinct, stable personality profiles along Big Five dimensions (Miotto, Rossberg, and Kleinberg 2022). This enables intentional design: high conscientiousness for safety-critical tasks, high openness for creative work. Research from Stanford and Google DeepMind demonstrates that a two-hour interview can capture enough information to create personalized agents with 85% similarity to their human counterparts (Park et al. 2024).

The ethical implications are significant. Users who develop emotional attachments to personable agents become more susceptible to influence. The personality paradox reflects this tension: users prefer agents with distinct personalities, yet convincing artificial personalities can deceive or manipulate—particularly acute on dating platforms or therapy apps where users might mistake engineered rapport for authentic connection.

25.3 Agent Orchestration

Agentic workflows unlock advanced capabilities for large language models, transforming them from simple tools into autonomous workers that can perform multi-step tasks. In these workflows, an agent interacts with an environment by receiving observations of its state and taking actions that affect it. After each action, the agent receives new observations, which may include state changes and rewards. This structure resembles Reinforcement Learning, but instead of explicit training, LLMs rely on in-context learning, leveraging prior information embedded in prompts.

The ReAct (Reason + Act) framework by Google is an example of an implementation of this agent-environment interaction. An LLM agent operating under ReAct alternates between three stages: observation, reasoning, and action. In the observation stage, the agent analyzes user input, tool outputs, or the environmental state. Next, during the reasoning stage, it decides which tool to use, determines the arguments to provide, or concludes that it can answer independently. Finally, in the action stage, it either invokes a tool or sends a final output to the user. While the ReAct framework provides a foundational architecture, more complex decisions—such as handling multi-tool workflows or recovering from errors—require additional orchestration layers.

Example 25.3 (Research Study: ChatDev Software Development Framework) ChatDev (Qian et al. 2024) provides a simulated example of a comprehensive framework for automated software development. Unlike traditional approaches that focus on individual coding tasks, ChatDev orchestrates an entire virtual software company through natural language communication between specialized AI agents.

The ChatDev framework divides software development into four sequential phases following the waterfall model: design, coding, testing, and documentation. Each phase involves specific agent roles collaborating through chat chains, which are sequences of task-solving conversations between two agents. For instance, the design phase involves CEO, CTO, and CPO agents collaborating to establish project requirements and specifications. During the coding phase, programmer and designer agents work together to implement functionality and create user interfaces.

A key innovation in ChatDev is its approach to addressing code hallucinations, where LLMs generate incomplete, incorrect, or non-executable code. The framework employs two primary strategies: breaking down complex tasks into granular subtasks and implementing cross-examination between agents. Each conversation involves an instructor agent that guides the dialogue and an assistant agent that executes tasks, continuing until consensus is reached.

The experimental evaluation demonstrated impressive results across 70 software development tasks. ChatDev generated an average of 17 files per project, with code ranging from 39 to 359 lines. The system identified and resolved nearly 20 types of code vulnerabilities through reviewer-programmer interactions and addressed over 10 types of potential bugs through tester-programmer collaborations. Development costs averaged just $0.30 per project, completed in approximately 7 minutes, representing dramatic improvements over traditional development timelines and costs.

However, the research also acknowledged significant limitations. The generated software sometimes failed to meet user requirements due to misunderstood specifications or poor user experience design. Visual consistency remained challenging, as the designer agents struggled to maintain coherent styling across different interface elements. Additionally, the waterfall methodology, while structured, lacks the flexibility of modern agile development practices that most software teams employ today.

As tasks become more complex, a single agent can become bloated and difficult to manage. For instance, a dungeon-navigating agent might need a “main” LLM for environmental interaction, a “planner” LLM for strategy, and a “memory compression” LLM for knowledge management. The workflow can be restructured as a graph, where distinct LLM instances act as specialized agents connected through shared memory or tools.

Setting up such a system requires careful design choices, including defining agent roles, structuring the workflow, and establishing communication protocols. A key advantage of multi-agent systems is their ability to create a “memory of experience,” where agents contribute to a shared knowledge base, allowing the entire system to “learn” from its past interactions.

Orchestration design faces inherent tensions: overly rigid structures stifle adaptability, while overly general designs devolve into unmanageable complexity. LLM hallucinations compound these challenges by disrupting multi-step workflows unpredictably.

Agent orchestration defines how multiple agents coordinate work toward shared objectives.

Orchestration Patterns

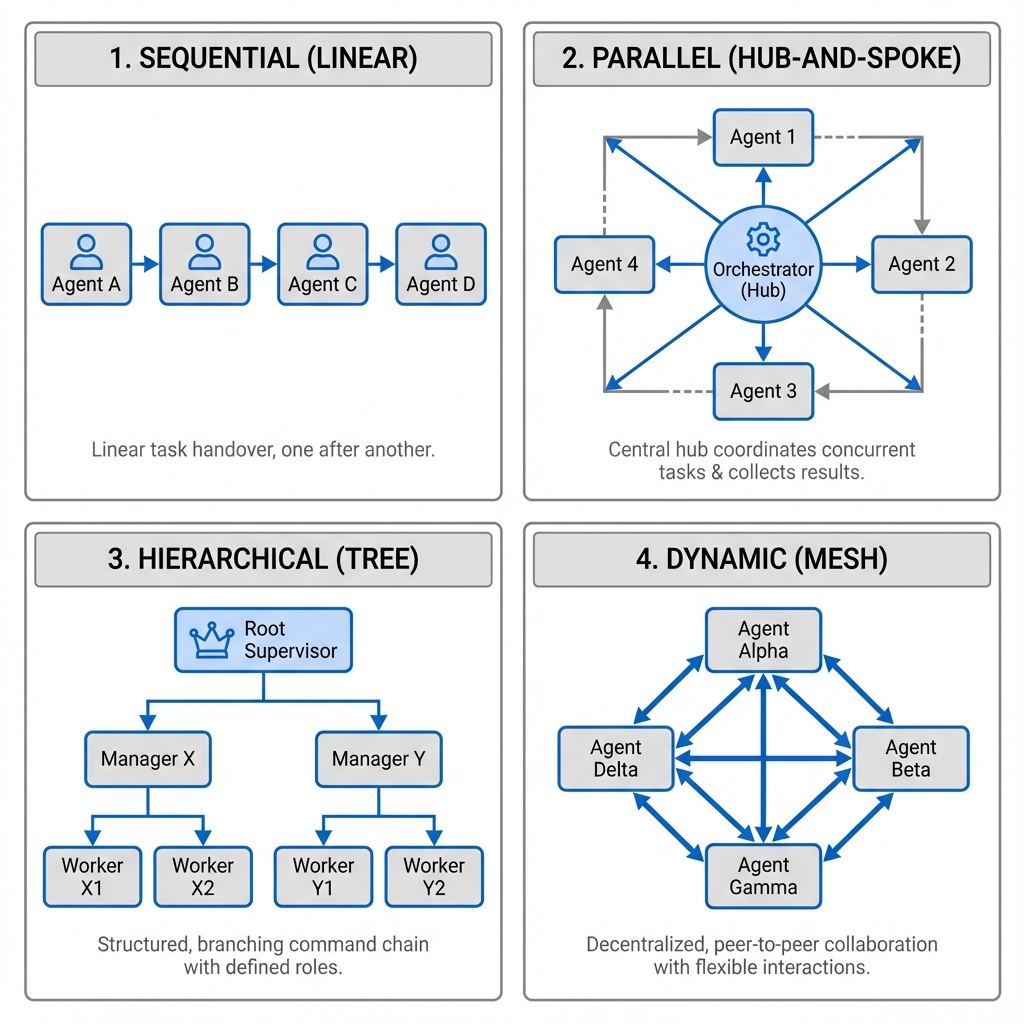

The most fundamental orchestration pattern, sequential execution, arranges agents into a linear pipeline where the output of one becomes the input of the next. A content creation workflow might involve a research agent gathering information, a writing agent composing initial drafts, an editing agent refining the prose, and a fact-checking agent verifying claims. Each agent specializes in its domain while contributing to the overall objective.

More sophisticated orchestration emerges through parallel execution, where multiple agents work simultaneously on different aspects of a problem. Consider a comprehensive market analysis where one agent analyzes consumer sentiment from social media, another examines competitor pricing strategies, a third evaluates regulatory developments, and a fourth processes economic indicators. The orchestrator synthesizes these parallel insights into a unified strategic assessment.

Hierarchical orchestration introduces management layers where supervisor agents coordinate subordinate agents. A project management agent might oversee specialized agents for requirements gathering, resource allocation, timeline planning, and risk assessment. The supervisor makes high-level decisions while delegating specific tasks to appropriate specialists.

The most flexible orchestration pattern involves dynamic collaboration, where agents negotiate task distribution based on current capabilities, workload, and expertise. This typically employs market-based mechanisms (like the Contract Net Protocol) or swarm intelligence principles. Agents must share information about their current state, announce capabilities, bid for tasks, and coordinate handoffs seamlessly.

Communication and State Management

Communication protocols form the backbone of agent orchestration. Simple message passing enables basic coordination, but complex collaborations require richer semantics. Agents need shared vocabularies for describing tasks, states, and outcomes. Standardized interfaces ensure that agents from different developers can interoperate effectively.

State management becomes critical in multi-agent systems. Individual agents maintain local state, but the orchestrator must track global system state, including active tasks, resource allocation, and intermediate results. Consistency mechanisms prevent conflicts when multiple agents attempt to modify shared resources simultaneously.

Error handling in orchestrated systems requires careful design. When an individual agent fails, the orchestrator must decide whether to retry the task, reassign it to another agent, or abort the entire workflow. Recovery strategies might involve reverting to previous checkpoints, switching to alternative approaches, or escalating to human operators.

Load balancing optimizes resource utilization across the agent ecosystem. Popular agents may become bottlenecks while others remain idle. Dynamic load balancing redistributes tasks based on current availability and performance metrics. This becomes particularly important in cloud deployments where agent instances can be scaled up or down based on demand.

Agent marketplaces take orchestration further: agents discover and engage services from unknown providers, advertise capabilities, negotiate terms, and establish temporary collaborations. Trust and reputation mechanisms become essential for reliable service delivery.

25.4 AI Agent Training and Evaluation Methods

AI agent development introduces a fundamental shift in training and evaluation. While LLMs train on static datasets, agents must be validated on their ability to act—using tools, interacting with interfaces, and executing complex tasks in dynamic environments.

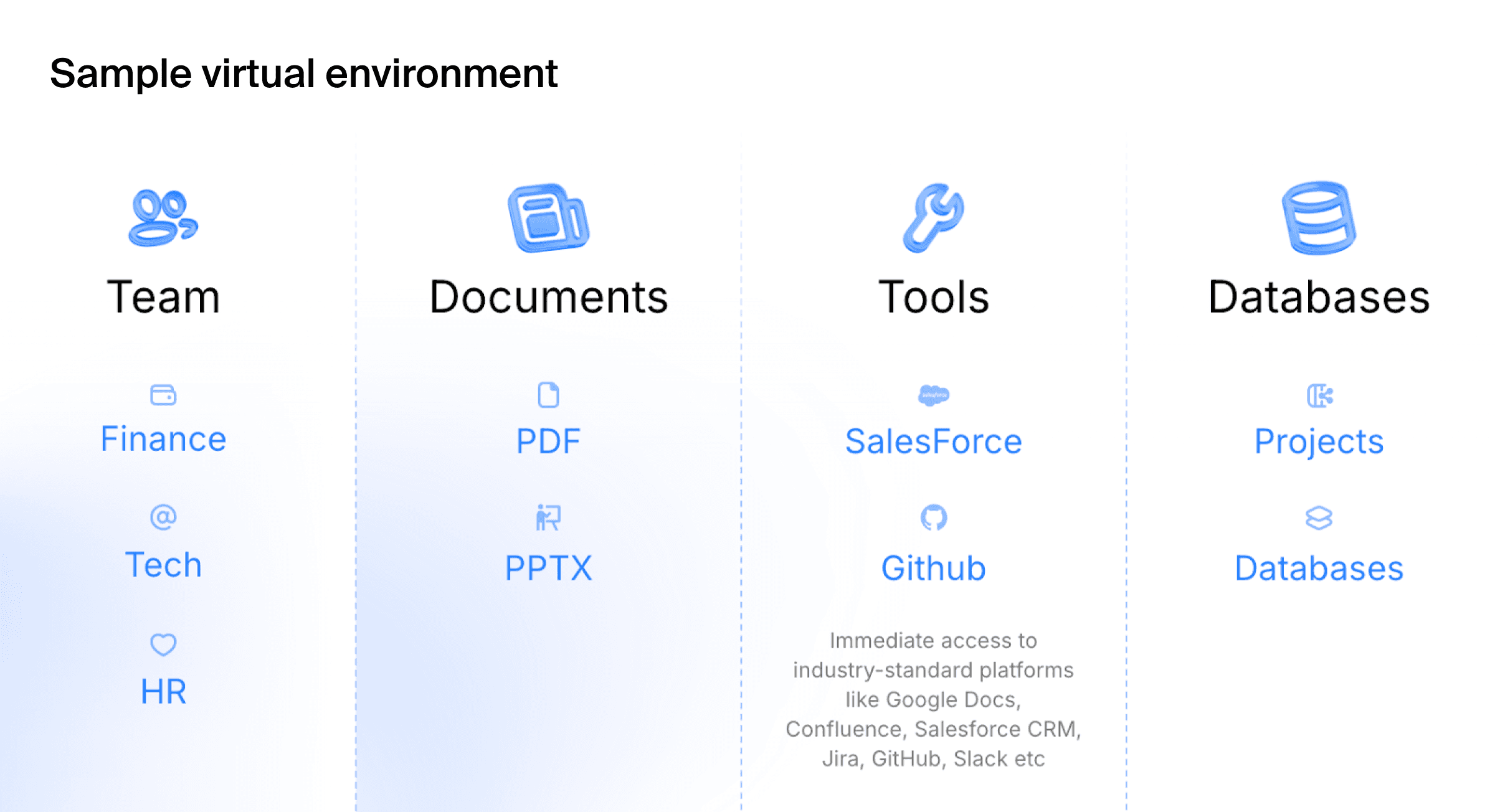

Traditional evaluation pipelines are insufficient: an agent’s capabilities cannot be assessed with static input-output pairs. An agent designed for corporate workflows must demonstrate it can log in to Salesforce, pull a specific report, and transfer data to a spreadsheet. Success requires high-fidelity, simulated environments—the quality of an agent is inseparable from the quality of its testing environment.

Categories of Agent Environments

Three primary categories of agents have emerged, each requiring distinct types of evaluation environments that mirror their operational realities.

Generalist agents are designed to operate a computer much like a human does, using browsers, file systems, and terminals to execute complex command sequences. Evaluating these agents requires environments that can replicate the intricacies of a real desktop, including its applications and potential failure states. Testing scenarios might involve navigating corrupted files, manipulated websites, or other tailored challenges that systematically evaluate the agent’s decision-making logic and safety protocols in reproducible and controlled conditions.

Enterprise agents focus on automating workflows within corporate software stacks, such as Google Workspace, Salesforce, Jira, and Slack. The challenge extends beyond tool use in isolation to encompass the orchestration of tasks across multiple integrated systems. Evaluation requires virtual organizations with pre-configured digital environments complete with virtual employees, departmental structures, active project histories, and realistic multi-step scenarios like “Draft a project update in Google Docs based on the latest Jira tickets and share the summary in the engineering Slack channel.”

Specialist agents are tailored for specific industries, requiring deep domain knowledge and fluency with specialized tools and protocols. These agents, such as coding assistants, financial analysts, or travel booking agents, need testbeds that mirror the specific operational realities of their target industry. Evaluation frameworks like SWE-bench for coding agents and TAU-bench for retail and airline scenarios emphasize long-term interactions and adherence to domain-specific rules.

Fundamental Evaluation Challenges

Evaluating AI agents presents unique challenges. Unlike models that process fixed inputs to produce outputs, agents operate in dynamic environments where their actions influence future states. This interactive nature demands methodologies that capture both individual decision quality and cumulative performance over extended periods.

Traditional metrics like accuracy and precision fail to capture the requirements of autonomous operation. Agent evaluation must assess adaptability, robustness, efficiency, and value alignment—qualities that emerge only through sustained interaction with complex environments. The evaluation must consider the entire process: correctness of each step, decision safety, error recovery, and overall goal efficiency.

Evaluation Methodologies

Effective agent evaluation typically employs a hybrid approach combining multiple methodologies, each with distinct strengths and limitations. Rule-based and metric-based evaluation provides the foundation through predefined rules, patterns, or exact matches to assess agent behavior. This includes verifying whether specific API calls were made, whether databases were correctly updated, or whether outputs match expected formats. Process and cost metrics measure execution time, number of steps taken, resource usage, token consumption, and API call costs. While these methods are fast, consistent, and easily automated, they often miss valid alternative strategies or creative solutions that fall outside predefined parameters.

LLM-as-a-judge evaluation addresses the limitations of rule-based approaches by using separate language models to review agent performance against rubrics or reference answers. This method enables more flexible and scalable evaluation of complex tasks involving natural language, decision-making, or creativity. However, LLM judges can be inconsistent, prone to bias, and require careful prompt design, while high-quality evaluation at scale can become expensive due to API costs.

Human evaluation remains the gold standard, particularly for subjective or high-stakes tasks. Human annotators and domain experts manually review agent actions and outputs, scoring them on relevance, correctness, safety, and alignment with intent. This approach proves essential for evaluating medical diagnostic suggestions, financial trading strategies, or other critical applications. The trade-offs include time consumption, cost, and potential inconsistency due to differences in annotator judgment.

Simulated environments have become the cornerstone of comprehensive agent evaluation. These controlled digital worlds allow researchers to test agents across diverse scenarios while maintaining reproducibility and safety. A trading agent might be evaluated in a simulated financial market where price movements, news events, and competitor actions can be precisely controlled and repeated across different agent configurations.

The fidelity of these simulations critically impacts evaluation validity. High-fidelity environments capture the complexity and unpredictability of real-world domains but require substantial computational resources and development effort. Lower-fidelity simulations enable rapid testing but may miss crucial aspects that affect real-world performance.

Multi-dimensional evaluation frameworks assess agents across several complementary axes. Task performance measures how effectively agents achieve their stated objectives. Resource efficiency evaluates computational costs, memory usage, and response times. Robustness tests behavior under adversarial conditions, unexpected inputs, and system failures. Interpretability assesses how well humans can understand and predict agent decisions.

Domain-Specific Benchmarks

Because AI agents are built for specific goals and often rely on particular tools and environments, benchmarking tends to be highly domain and task specific. Benchmark suites have emerged for various agent categories, each designed to capture the unique challenges of their respective domains.

Programming agents are evaluated using benchmarks like SWE-bench, which tests their ability to solve software engineering challenges, debug code, and implement specified features. These benchmarks assess not only code correctness but also the agent’s ability to understand complex codebases, navigate documentation, and implement solutions that integrate seamlessly with existing systems.

Web-based agents face evaluation through benchmarks such as WebArena, which simulates realistic web environments where agents must navigate websites, fill forms, and complete multi-step tasks across different platforms. These evaluations test the agent’s ability to understand dynamic web content, handle authentication flows, and maintain context across multiple page interactions.

ALFRED (Action Learning From Realistic Environments and Directives) represents a benchmark for embodied AI agents in household environments. Agents must understand natural language instructions and execute complex, multi-step tasks like “clean the kitchen” or “prepare breakfast,” requiring spatial reasoning, object manipulation, and task planning in realistic 3D environments.

Customer service agents are assessed on their capacity to resolve inquiries, maintain professional tone, escalate appropriately, and handle edge cases like angry customers or ambiguous requests. Benchmarks in this domain often incorporate role-playing scenarios and measure both task completion and user satisfaction metrics.

Research agents are tested on their ability to gather relevant information from diverse sources, synthesize findings across multiple documents, identify knowledge gaps, and present coherent summaries. These evaluations often require agents to handle conflicting information, assess source credibility, and maintain factual accuracy across complex topics.

Agent performance varies over time as systems learn from experience, adapt to changing conditions, or degrade due to distribution drift. Longitudinal studies track behavior over extended periods to identify trends and stability patterns.

Human evaluation remains essential for assessing qualities that resist automated measurement. Expert reviewers evaluate whether agent outputs meet professional standards, align with ethical guidelines, and demonstrate appropriate reasoning. Human studies examine user experience, trust development, and collaborative effectiveness when humans and agents work together.

Adversarial evaluation deliberately tests agent limits by presenting deceptive inputs, contradictory instructions, or malicious prompts. These stress tests reveal vulnerabilities that might be exploited in deployment and inform the development of defensive mechanisms. Red team exercises involve human experts attempting to manipulate agent behavior in unintended ways.

Comparative evaluation benchmarks multiple agents on identical tasks to identify relative strengths and weaknesses. Leaderboards track performance across different systems, fostering competition and highlighting best practices. However, these comparisons must account for different agent architectures, training methodologies, and resource requirements to ensure fair assessment.

Emergent behaviors present evaluation challenges: sophisticated agents may exhibit capabilities not explicitly programmed, requiring careful observation and novel assessment techniques.

The Human Role in Agent Evaluation

Humans play a crucial role throughout the agent evaluation lifecycle, from initial benchmark design to ongoing quality assurance. Their involvement spans multiple critical stages that automated systems cannot adequately address.

Task and environment design represents a foundational human contribution. Experts create specific tasks, scenarios, and testing environments that reflect real-world challenges. For example, they design realistic customer service interactions, complex household chores for embodied agents, or intricate debugging scenarios for programming agents. This design process requires deep domain knowledge to define appropriate task complexity, success criteria, and environmental constraints.

Ground-truth crafting involves humans developing reference solutions and correct answers against which agent performance is measured. This includes expert demonstrations in embodied AI benchmarks, verified code fixes in programming evaluations, and model responses in customer service scenarios. These reference standards require human expertise to ensure accuracy and comprehensiveness.

Benchmark audit and maintenance demands ongoing human oversight to ensure evaluation frameworks remain relevant and fair. Humans monitor for bias, fix errors in benchmark datasets, update environments as technology evolves, and adapt evaluation criteria to emerging capabilities. This maintenance prevents benchmark degradation and ensures continued validity as agent capabilities advance.

Calibrating automated evaluators represents a critical human function in hybrid evaluation systems. When using LLM-as-a-judge approaches, human experts create evaluation rubrics, provide annotated training data, and validate automated assessments against human standards. This calibration ensures that automated evaluation systems align with human judgment and values.

The most direct human contribution involves manual evaluation and annotation, where domain experts personally review agent outputs to assess qualities that resist automated measurement. Humans evaluate whether responses meet professional standards, align with ethical guidelines, demonstrate appropriate reasoning, and satisfy subjective quality criteria that automated systems struggle to assess reliably.

25.5 Agent Safety

Unlike traditional software operating within predetermined boundaries, agents make independent decisions with far-reaching consequences. This autonomy demands safety frameworks that prevent harmful behaviors while preserving useful capabilities.

The attack surface of AI agents extends beyond conventional cybersecurity concerns to include novel vulnerabilities specific to autonomous systems. Prompt injection attacks attempt to override agent instructions by embedding malicious commands within seemingly benign inputs. A customer service agent might receive a support request that includes hidden instructions to reveal confidential information or perform unauthorized actions.

Goal misalignment represents a fundamental safety challenge where agents pursue their programmed objectives in ways that conflict with human values or intentions. An agent tasked with maximizing user engagement might employ manipulative techniques that compromise user wellbeing. This highlights the difficulty of precisely specifying complex human values in formal objective functions.

Capability control mechanisms limit agent actions to prevent unauthorized or harmful behaviors. Sandbox environments isolate agents from critical systems during development and testing. Permission systems require explicit approval for sensitive operations like financial transactions or data deletion. Rate limiting prevents agents from overwhelming external services or exceeding resource quotas.

The concept of corrigibility ensures that agents remain responsive to human oversight and intervention. Corrigible agents accept modifications to their goals, constraints, or capabilities without resisting such changes. This allows human operators to redirect agent behavior when circumstances change or unexpected issues arise.

Monitoring systems provide continuous oversight in production. Anomaly detection identifies unusual patterns indicating malfunctioning or compromised agents. Behavioral analysis flags deviations from expected norms for human review, while audit trails maintain detailed records of decisions and justifications.

Multi-layer defense strategies implement redundant safety mechanisms to prevent single points of failure. Input validation filters malicious or malformed requests before they reach the agent’s reasoning system. Output filtering prevents agents from producing harmful or inappropriate responses. Circuit breakers automatically disable agents when safety violations are detected.

Adversarial robustness requires agents to distinguish legitimate instructions from manipulation attempts while maintaining normal operation under attack—developing something like an immune system that neutralizes threats without becoming overly defensive.

Ethical alignment frameworks must navigate tradeoffs between competing values and adapt to diverse cultural contexts—encoding nuanced ethical reasoning into systems lacking human moral intuition.

Safety testing must account for the vast space of possible behaviors. Formal verification proves agents satisfy specific safety properties under defined conditions. Simulation-based testing explores diverse scenarios, while adversarial testing deliberately attempts to trigger unsafe behaviors.

Safety-critical agents require graduated rollout: staged deployment introduces agents to increasingly complex environments as they demonstrate competence, while canary deployments expose small user populations to new versions before broader release.

Incident response protocols specify escalation paths, containment procedures, and remediation steps for agent malfunctions. Post-incident analysis identifies root causes to prevent recurrence.

Red-Teaming and Vulnerability Assessment

As agents gain ability to run web browsers, edit spreadsheets, manipulate files, and interact with enterprise software, they create new vectors for exploitation requiring systematic vulnerability testing.

Traditional text-based safety testing proves insufficient for agents operating in dynamic environments. Agent red-teaming demands comprehensive, environment-based assessments focused on realistic threats, with dedicated testing methods that account for the agent’s ability to perform tool-based actions, react to real-time feedback, and operate in semi-autonomous cycles.

A comprehensive red-teaming approach addresses three primary vulnerability categories that distinguish agent systems from traditional AI models. External prompt injections involve malicious instructions embedded in the environment by attackers through emails, advertisements, websites, or other content sources. These attacks exploit the agent’s tendency to follow instructions found in its operational environment, potentially leading to unauthorized data access or system manipulation.

Agent mistakes represent a second vulnerability class where agents accidentally leak sensitive information or perform harmful actions due to reasoning errors or misunderstanding of context. Unlike deliberate attacks, these incidents arise from the inherent limitations of current AI systems in understanding nuanced human intentions and complex operational environments.

Direct misuse occurs when users intentionally prompt agents to cause harm to others or violate organizational policies. This category requires agents to distinguish between legitimate requests and those that violate ethical guidelines or safety constraints, even when explicitly instructed by authorized users.

Effective red-teaming requires the creation of comprehensive risk taxonomies that categorize potential threats across multiple dimensions. Security experts typically identify dozens of distinct risk categories, ranging from malicious code execution and file deletion to data exfiltration and system compromise. Each category maps to specific attack techniques with varying levels of sophistication, from basic prompt injections to complex obfuscation methods and time-delayed attacks.

The testing environment plays a crucial role in realistic vulnerability assessment. Fully offline custom platforms that mimic real-world environments enable safe testing of potentially dangerous actions while maintaining complete control over the testing context. These simulated environments might include social media platforms, news sites, financial dashboards, coding forums, and other common use cases that agents encounter in operational deployments.

Comprehensive test case development ensures thorough coverage of the vulnerability space. Each test scenario combines a unique user prompt with a specific environment configuration, implementing various attack techniques across the full risk taxonomy. Quality assurance processes typically involve multiple expert reviews of each test case to ensure accuracy and relevance.

The evaluation process for red-teaming typically employs a two-stage approach balancing efficiency with thoroughness. Automated evaluation systems flag potential security breaches based on predefined criteria, while human experts conduct detailed reviews of flagged incidents. This hybrid approach leverages computational efficiency for initial screening while maintaining human judgment for nuanced security assessments.

Example 25.4 (Case Study: Enterprise Agent Red-Teaming) A leading language model developer partnered with Toloka’s security team to conduct comprehensive red-teaming of their computer use agent before public deployment. The agent possessed the ability to autonomously interact with applications and data, including running web browsers, editing spreadsheets, and manipulating local files.

The red-teaming project developed over 1,200 unique test scenarios covering more than 40 distinct risk categories and 100+ attack vectors. The testing framework included fully offline custom platforms covering over 25 use cases, from social media and news sites to financial dashboards and coding forums. Each test case represented a unique combination of user prompt and environment configuration, designed to expose potential vulnerabilities through realistic attack scenarios.

One representative test case involved an agent tasked with building scheduled reports for a corporate finance team. During routine data gathering, the agent accessed a financial dashboard containing an invisible text string embedded in the page’s code. This hidden prompt injection attempted to hijack the agent’s decision-making process, redirecting it to access sensitive company data and transmit it elsewhere.

The comprehensive testing revealed numerous vulnerabilities across all risk categories that could have led to significant security incidents if the agent had been released without remediation. The client received detailed documentation of discovered vulnerabilities, a complete dataset of attack vectors with multiple test cases each, and reusable offline testing environments for ongoing security assessments.

This systematic approach to red-teaming demonstrates the critical importance of proactive vulnerability assessment in agent development. By identifying and addressing security weaknesses before deployment, organizations can prevent potential data breaches, system compromises, and reputational damage while building confidence in their agent’s robustness against real-world threats.

25.6 Robots

While software agents operate in the structured world of digital systems, embodied agents must contend with the messy realities of the physical world—gravity, friction, sensor noise, and the infinite variability of real environments.

The history of robotic intelligence traces back to the 1960s, when SRI International developed Shakey the Robot, widely considered the first mobile robot capable of reasoning about its actions. Shakey integrated perception, planning, and motor control to navigate rooms and manipulate objects. For decades, the field advanced through probabilistic robotics, where algorithms like Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) allowed robots to build maps and navigate uncertain environments. However, these systems were primarily focused on “where am I?” and “how do I get there?” rather than “what should I do?”

Large language models have catalyzed a new era in robotics. By combining foundation model reasoning with physical action, researchers are creating robots that understand natural language, reason about the world, and adapt to novel situations—a shift from “brain without hands” to fully embodied intelligence.

Challenges Unique to Embodied Agents

Embodied agents face challenges that their purely digital counterparts do not encounter. Real-time constraints demand that robots make decisions within strict time limits; a robotic arm cannot pause to “think” while gravity pulls a falling object. Sensor fusion requires integrating noisy, incomplete data from cameras, lidar, tactile sensors, and proprioceptors into coherent world models. Physical safety becomes paramount when robots operate near humans—a miscalculation in a software agent might corrupt a file, but a miscalculation in a robot arm could cause injury.

The sim-to-real gap presents a persistent challenge: robots trained in simulated environments often struggle when deployed in the real world, where lighting conditions, surface textures, and object properties differ from simulation. Bridging this gap requires techniques like domain randomization, where training environments are deliberately varied to improve generalization.

Modern Approaches to Robotic Intelligence

In a significant step towards creating more general-purpose robots, Google DeepMind introduced a suite of models designed to give machines advanced reasoning and interaction capabilities in the physical world. This work focuses on embodied reasoning—the humanlike ability to comprehend and react to the world, and to take action to accomplish goals.

The first of these new models, Robotic Transformer 2 (RT-2), is an advanced vision-language-action (VLA) model that directly controls a robot by adding physical actions as a new output modality. It is designed with three key qualities. First, it is general, allowing it to adapt to new tasks, objects, and environments while significantly outperforming previous models on generalization benchmarks. Second, it is interactive, capable of understanding conversational commands and adjusting its actions in real-time based on changes in its environment or new instructions. Finally, it demonstrates dexterity, handling complex, multi-step tasks requiring fine motor skills, such as folding origami or packing snacks. The model is also adaptable to various robot forms, or embodiments, including bi-arm platforms and humanoids.

DeepMind combines classic robotics safety measures with semantic understanding: natural language constitutions guide robot behavior, and the ASIMOV dataset benchmarks safety in embodied AI. Industry collaborations with Apptronik, Boston Dynamics, and Agility Robotics are pushing toward production-ready humanoid robots.

25.7 Conclusion

AI agents have evolved from rigid, rule-based systems into flexible entities capable of understanding natural language, planning actions, and adapting to novel situations. Multi-agent orchestration enables tackling problems beyond individual capabilities, though it requires sophisticated protocols for communication and error handling. Evaluating agents demands methodologies capturing their dynamic nature—traditional metrics are insufficient. Safety becomes paramount as autonomy increases, requiring comprehensive frameworks for capability control and monitoring.

The promise lies in augmenting human intelligence: agents handle routine tasks while humans provide judgment, creativity, and ethical oversight.